Christian Socialist Bruce Wallace Sets Out Vision for the New Northern Ireland State

19 April 1921

Northern Whig, 21 April 1921

On 19 April 1921, the Rev. Bruce J. Wallace addressed a pre-election meeting in Belfast on the future of self-government for Northern Ireland. A Protestant dissenter, Wallace was a Christian Socialist and founded the radical newspaper ‘The Brotherhood’ in Limavady in 1887. The paper’s radical and socialist ideals would find their clearest practical expression in Wallace’s Brotherhood Church, which he established in London’s Southgate Road Chapel in the 1890s. He was one of the founding members of the Fabian Society and the first secretary of the Democratic Club, working alongside Keir Hardie and Ramsay MacDonald.

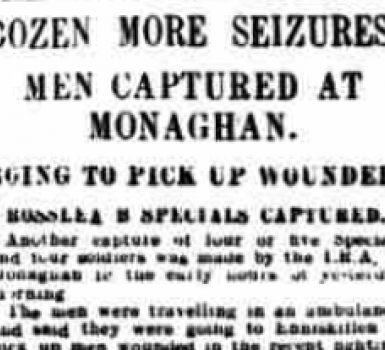

Wallace’s socialism was also heavily influenced by the leading light of the northern labour movement Harry Midgley, and both men stood as independent labour candidates at the 1921 election to the new Northern Ireland parliament. Though a Protestant Unionist himself, Midgley along with two of the other labour activists fought the election on an anti-partitionist platform. They received Loyalist intimidation and violence throughout their campaign and secured few votes, falling victim to the Unionist leadership’s attempt to marginalise the Belfast Labour Party’s influence. Wallace, on the other hand, upheld the right of Ulster Protestants not to be forced under an all-Ireland parliament and received 926 first preference votes in North Belfast, the largest vote of the four Labour candidates.

Self-Government: Rev. Bruce Wallace’s Suggestions

On Tuesday night a meeting was held in the Artisans’ Hall, Garfield Street, at which the Rev. Bruce J. Wallace, M.A., spoke on “What Use Should Ireland Make of Self-Government?” There was a very large attendance.

Rev. Mr. Wallace said the first duty of any Government was to secure, as far as its action could, that all citizens should have conditions in which they might live out their lives to their natural and normal conclusion in old age healthily and happily. Preventable diseases and deaths among them were innumerable. Noxious germs were generated in the slums, and not only created havoc there but invaded the homes of the comfortable classes, who had thus to pay a penalty for their share in the community's neglect of the poor.

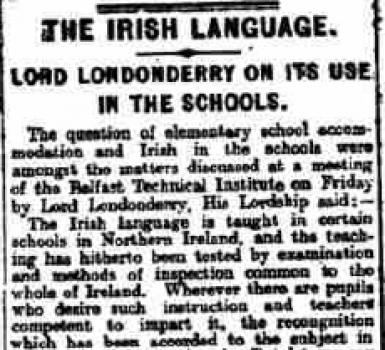

Next to the duty of keeping the children alive and healthy came the task of educating them to the fullest development of their powers, and especially for their moral natures. Willingness to make great sacrifices for the purpose of helping the rising generation up to its highest possibilities was the one sure test of a community’s civilisation.

Another was the status and honour it accorded to its women. The programme of the Belfast Women’s Citizens’ Council, which seeks to promote justice towards women in every respect and proper care for child-life, well deserved the consideration of their future Irish legislators. The temperance party’s demands for some restrictive legislation, which were being grotesquely exaggerated and misrepresented by the liquor party, were sadly necessary under present conditions.

On the other hand, the fundamental, principal, and central measure of industrial and economic reconstruction most urgently required, which would gradually do away with unemployment and secure to all workers a freedom of contract they had never hitherto enjoyed, would not necessarily cost the community anything, though it would require Government credit for obtaining land and capital with which to start….

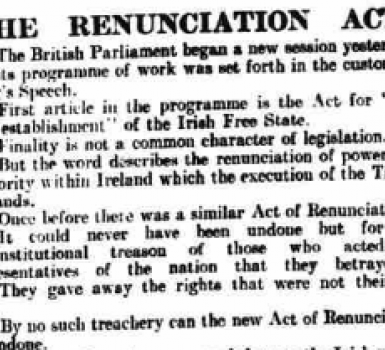

Now was the time for Northern Ireland to break away from old traditions. It had got its opportunity for reconstructing its social order—imperfect indeed —but it gave scope for showing what conscience and goodwill were in it. However a movement in that direction might be opposed by men with vested interests in the poverty and dependent positions of some of their neighbours, it would surely commend itself to the common sense and to the moral sense, of all thinking people.