Northern Parliament and Craig's Election Campaign Criticised

05 May 1921

Dublin Evening Telegraph, 5 May 1921

Following the commencement of the Government of Ireland Act on 3 May 1921, Irish newspapers speculated on what its implementation might mean for the two new Home Rule states of Northern and Southern Ireland. In this editorial, the Dublin Evening Telegraph questioned the claims that Sir James Craig made to his supporters, raised doubts about the fairness of the upcoming 1921 Northern Ireland general election, and stated that the proclamation summoning a Southern parliament was ‘an empty form which mocks reality’.

Free or Fettered?

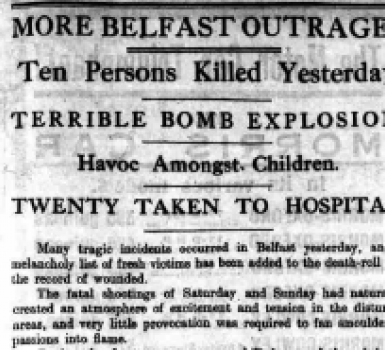

The proclamations summoning the Partition “Parliaments” have been signed and Lord Fitzalan of Derwent has returned to England. The nominations will take place next Thursday and the polling is fixed for May 21st. In the North, the Unionist election campaign is in full blast, and Sir James Craig has been delivering himself of speeches which are not particularly inspiring to crowded meetings of his supporters.

He has been telling them that the Partition Act confers on them “the status of a State with its own capital,” and he calculates that this will mean the introduction to Belfast, within a limited number of years, of an additional population of from thirty to fifty thousand, which would not be attributable to the ordinary growth of the city. Moreover, he said, the status of a capital meant increased credit, “and upon credit the whole fabric of business and society rested, and upon that credit also the welfare in the long run and the prosperity of the great mass of the working classes.”

Business men in Belfast will not be much impressed with the promise of prosperity to come through the medium of an administration which will be bankrupt from its very inception. If they take the trouble of studying the Partition Act for themselves, they may come to a conclusion which cannot be reconciled with Sir James Craig’s rosy forecast.

The industrial workers of Belfast who are not absolutely blinded to their own interests by appeals to sectarian passion may also be sceptical about the future before them in a section of a province which is isolated from the country to which it belongs. However, the elections to the Northern “Parliament” are to take place, and that under conditions which differ entirely from those prevailing in the 26 counties. The right of public meeting is not suspended in the North, except for supporters of the Republican candidates. For the Orangeman speech is free, and Mr. Twaddell has nothing to fear when he declares that the appointment of a Catholic Lord Lieutenant is contrary to the British Constitution.

Sir James Craig challenges the Sinn Féin candidates to state their programme, although he knows that many of them are in jail, others “on the run,” and all of them prevented from speaking on a public platform, save at the imminent risk of being imprisoned. Nor can he be unaware of the probability that Nationalist and Sinn Féin voters alike will have to run the gauntlet on the polling day of organised mobs of Orangemen, not to speak of the armed “special constables,” who will be on duty to ensure the “free and unfettered” exercise of the franchise by their friends.

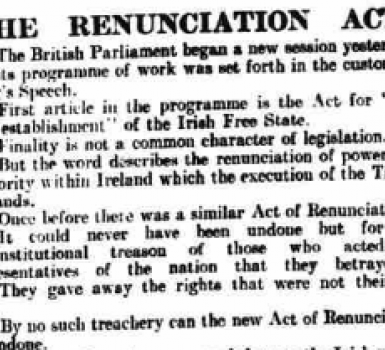

Outside the Six Counties, and especially in the Martial Law area, the elections will be conducted under conditions which could not be paralleled in any other country under the sun. No public meeting can be held; canvassing will be impossible; the discussion of questions of vital importance to the community at large will be tabooed. The proclamation summoning the “Parliament of Southern Ireland” is, in the circumstances, an empty form which mocks reality. The “free and unfettered” exercise of the franchise under a grinding military despotism is impossible, and so it was meant to be by the Government who are trying to perpetrate this fraud upon the Irish people.