David Lloyd George Addresses Commons on Irish Question

20 August 1921

The Times, 20 August 1921

Following the end of the Irish War of Independence, David Lloyd George met Éamon de Valera in London four times to discuss the Irish situation, and then later sent on his initial proposals to the Sinn Féin leader. In August, two months before the beginning of Anglo-Irish negotiations, David Lloyd George addressed the House of Commons on the Irish situation, stating that there was no further room for negotiation.

IRISH TERMS FINAL

WESTMINSTER, Friday.

In carefully chosen language and deliberately weighed words the PRIME MINISTER to-day made a statement to the Commons on the Irish situation. He sought to convince the Irish people that the offer which has been put forward by the Government is a genuine offer, that it represents a whole-hearted attempt to secure peace and the good will of the Irish people, and that the outline of those terms cannot be altered nor the basis changed.

Mr. LLOYD GEORGE was anxious to make it clear that they were not “haggling” terms, and he stated that he had heard of no suggestions from any quarter in this country or from any part of the world except Ireland that we had not gone to the very limits of possible concessions. Indeed, there were those who said we had gone too far. The Prime Minister made it clear to all the world that in the letters to Mr. de Valera the Government had placed all their cards on the table. They had done so because of the importance of ranging on the side of the proposals all sane opinion, not merely in this country and in Ireland, but throughout the world.

TWO CONTINGENCIES

Only two contingencies could arise; either there would be agreement or there would be a definite rupture. In the case of agreement being arrived at they would have to thrash out the details. That undoubtedly would take time. When all details were agreed upon a Bill would have to be framed, and as soon as that was done it would be the duty of the Executive to take steps immediately to place that Bill before Parliament, to submit it to the judgement of Parliament and the country, and to invite Parliament to give it legislative enactment without delay.

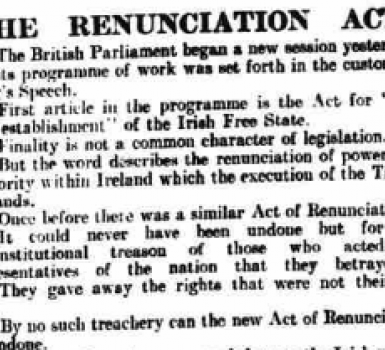

Reluctantly the Prime Minister had to take into account the other contingency. Were that final misfortune to befall the relations between these two islands, whose history has been so full of such unfortunate incidents, we should be faced with a graver situation in regard to Ireland than any with which we had been confronted. The terms had at all events defined the issues more clearly than they had ever been defined before. Their rejection would be an unmistakable challenge to the authority of the Crown and the unity of the Empire near the very heart of it, and no party in the State could possibly pass that over without notice.

IN CASE OF NEED

If there were a final rejection of terms beyond hope, steps would undoubtedly have to be taken which the Executive would not wish to take without consulting Parliament. The position of Parliament, therefore, would be that if agreement had been reached by October 18, or if negotiations were proceeding satisfactorily, the House would meet only for formal purposes. If the negotiations broke down, and the position was hopeless, as far as any chance of agreement was concerned, the Speaker would be authorized, after consultation with the Government, to summon Parliament at 48 hours’ notice. Emergency measures might be necessary even before Parliament met, but there would be no delay in summoning Parliament.

The Government (said the Prime Minister, in conclusion) are sincerely desirous that peace should ensue, that the long misunderstandings should be brought to an end. In spite of disquieting facts, I hope reason will prevail even over logic, and that the Irish leaders will not reject the largest measure of freedom ever offered to their country and take the responsibility of renewing a conflict which would be robbed of all glory and all gratitude by its overshadowing horror…