Ireland and the World

08 October 1921

Anglo-Celt, 8 October 1921

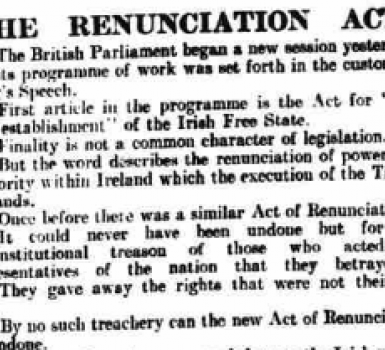

If the First World War marked the height of British Imperial power, Ireland’s treaty negotiations in 1921 could be seen as part of the empire’s decline. A colonial state rebelling against their London government (either by force or non-violent protest) and subsequently gaining a form of independence became a relative staple of the British colonial experience from the 1920s onwards. Some publications saw the writing on the wall as the negotiations for Irish independence were about to take place. In this editorial, the Anglo-Celt ponders the potentially far-reaching implications should Ireland successfully detach itself from the British Empire. Interestingly, it considers the possibility of a settlement a likely boon to Britain’s reputation, economy and international diplomacy.

Why The Irish Question Affects The World

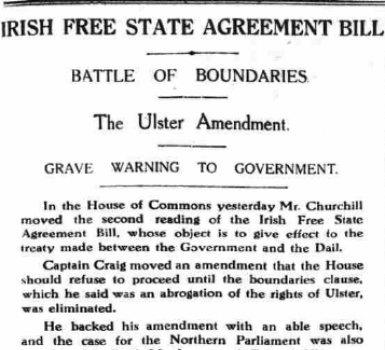

If the Conference between the Irish plenipotentiaries in London the 11th inst. and the representatives of the British Government has a satisfactory and speedy termination it will go a great way towards solving the other great issues which are threatening the world to-day. The case made out for this country is known to the people of the wide earth, but no one, so far as we are aware, has pointed out how a settlement would benefit England. To take the question of disarmament, in connection with which President Harding has issued an invitation to the other Powers for November 11th, there can be no free action by Britain unless the world is satisfied that the Irish question is solved, and for this reason. The Alliance between the United Kingdom and Japan is hanging in the balance, but has not been reaffirmed, and never will be if such an understanding can be arrived at between England and the United States as will ensure that for the future they are to stand by each other. With an agreement of this character in existence the latter country could cease at once the building of war vessels which has become necessary to keep pace with Japanese activity, and both Canada and Australia, which are looking to America in their peril, would feel secure that the danger of Japanese invasion, which threatens them as it does the United States, was at an end. Furthermore, the indebtedness of the nations in connection with the war could be wiped off the slate, as a merchant blots out a bad debt, thus allowing the various countries to set their unemployed to work at peaceful output, with free and normal exchange of goods which can neither be manufactured nor sold at present because of the existing rate of exchange. To cite an example, Germany, cannot purchase from either Britain or America when it takes 480 marks instead of 20 to buy articles to the value of £1 – and the exchange as it affects some of the other European States is even worse. To make stable the affairs of the world just now would mean the highest mark of statesmanship, but this cannot, as we say, be effected until Britain can act with a full knowledge of what she is going, and this cannot be accomplished until the Irish claim is met in a way which will remove all doubts.

[…]

It will be therefore seen from the above brief analysis of the situation, that it is upon the Irish problem that most of the great questions of the world are at present hanging, and that for that reason it should be to the interest of the other Nations as well as of Britain to have the long drawn-out struggle in Ireland at last brought to a termination. As to the negotiations in London, we would say that if an agreement is come to between the representatives nominated by both sides, there should be a clear understanding from the very beginning, of immediate ratification. To put it another way – assuming that by this day fortnight all of the British Ministers at the Conference, with the concurrence of the Irish envoys, were to sign an agreement as to what this country was to receive, that document would carry with it no actual weight unless it had the sanction of the British Parliament. Having attached his name, Mr Lloyd George might be called to Washington and there, amidst the congratulations of the American people for having for all time ended the Irish difficulty, it might be told that an agreement between the United States and Britain had been arrived at – but on the Premier’s return to England the British Parliament might refuse to ratify what he and his conferrers had done – and then where would we find Ireland standing? It is because all sections and creeds in this country are desirous of a lasting settlement that every aspect of the case should be examined beforehand to prevent a culmination which could only mean disaster.