New Ideals of Feminine Beauty

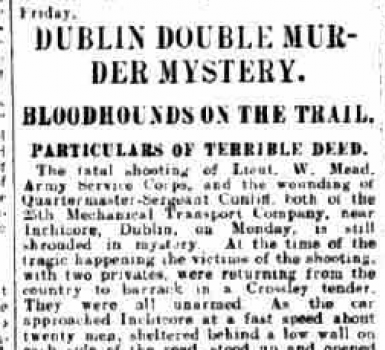

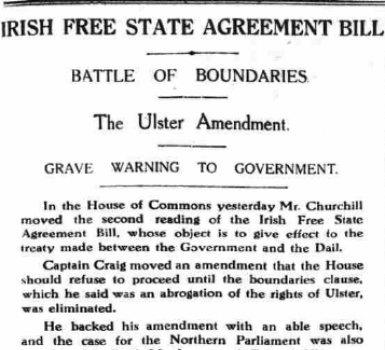

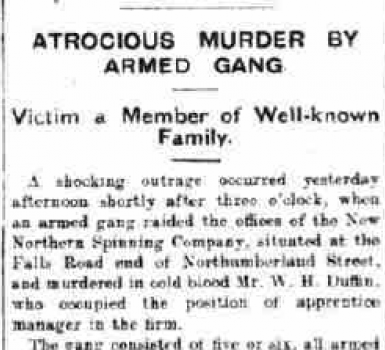

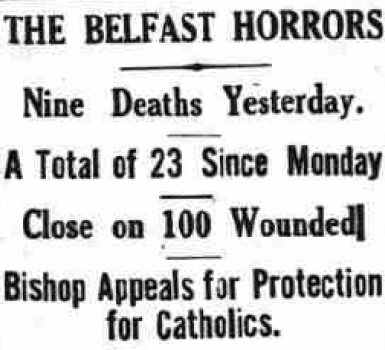

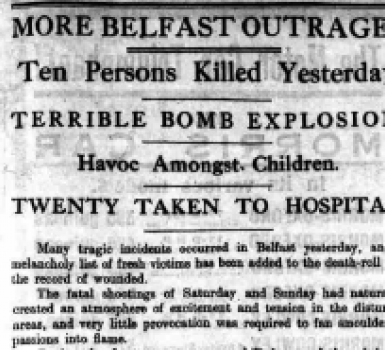

10 April 1921

Sunday Pictorial, 10 April 1921

The years after the end of the First World War saw bold new fashions emerge, particularly for women. The new styles were not always welcomed, as shown in this column from April 1921. The male author commented on how fashions had changed since the Victorian era and how, in the post-war years, youth was idealised above all other beauty standards.

New Ideals of Feminine Beauty: Youth and Audacity in Place of Dignity

By Wilson Macnair: Who says that the popular girlish type of woman today is symbolical of the passing of old ideas?

There is no doubt that our standard of woman’s beauty is changing.

I had thought so for some time, but a bunch of old magazines I found in a country house the other day dispelled the last doubt on the subject. They belonged to the period 1890–1892, and were illustrated with pictures of the beauties of that time.

The first impression was that ‘leg-of-mutton’ sleeves were an absurdity we are well rid of in more practical days. And then came a surprise – these women all looked much older than the new beauties, their daughters, look.

Once that idea possessed you the old magazines held a fresh interest. You turned from page to page to find out just how old the ladies of the sleeves might have been when they were adjudged to be types of English loveliness. Apparently very young: for here was one, labelled ‘Society’, of nineteen … and here was a popular actress of that time whose success was advertised as a ‘triumph of youth’. Her age was eighteen.

They all looked twenty-five or even thirty – at a casual glance. If you cut a sheet of note paper, however, in such a way as to exclude the clothes and leave only the faces visible and superimposed it on the pictures they looked much, much younger. The age was in the clothes. … Actually, they were trying to look grown-up and mature. Girlishness evidently was at a discount.

… But it does not follow in the least that this is a bad sign or a sign of the adoption of false standards of beauty. It only means that for the moment mankind believes in youth more than it believes in maturity. We may even, without straining a point, carry the matter further and say that it means that the hope in the world is stronger and more abundant than the faith.

For if we look round we see that it is not only youth in woman’s beauty that is admired at present, but youth in woman’s beauty that is admired at present, but youth in all beauty. The ‘fat landscape’ of Victorian art is gone; our modern landscape painters seek rather – the best of them at least – for that spiritual quality which is never quite in the form of things, never certainly in the mature form. … The girlish woman of to-day is no sign of decadence or a false standard of beauty. On the contrary, she reveals to us the new world that has utterly replaced the old.