Qualified optimism, but dark portents

08 December 1921

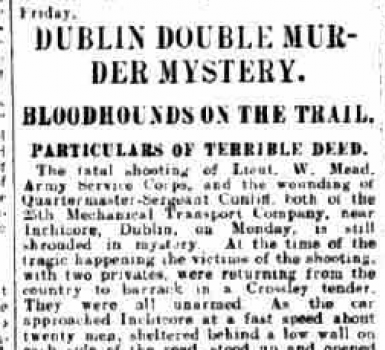

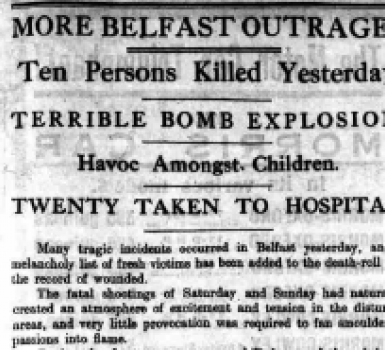

The Anglo-Irish Treaty was met with general celebrations across Ireland and Britain, but not total euphoria. Some observers could already see potential clashes due to the compromises made in the document. Others took a more fatalistic view of Irish history. This short history by Mary Mackay, published in the Freeman’s Journal shortly after the signing of the Anglo-Irish Treaty, lingers on the legacy of decades of war and wonders at the end whether peace can really last. Her article was printed next to a photograph of the signed Anglo-Irish Treaty.

Freeman’s Journal, 8 December 1921

THE UNBELIEVABLE PEACE

A Rift in the Lowering Clouds of Seven Centuries

(By MARY MACKAY.)

After seven hundred years of intermittent warfare, this seems impossible – peace, or the promise of it. After seven hundred years of cherished hatreds, sevenfold strange seems mutual effort towards amity, towards a friendship as deliberate as old hatreds have been. What has been the history of the past? Unceasing struggle.

Roderic O’Connor was the last king of united Ireland – and more than seven centuries have gone by since then. What a story of mixed shame and glory. The efforts to win over the Irish chiefs to the stranger, so largely successful, too, that when Henry VIII came along, things then “looked like peace”.

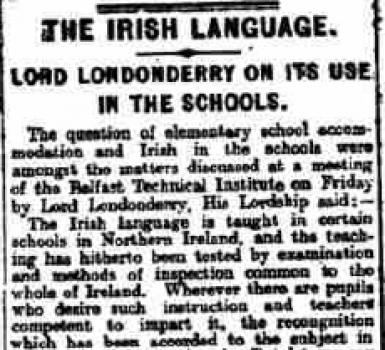

It seemed, indeed, that Ireland would be a loyal part of the dominions of the crown; but then other issues mingled with this of nation and nation. A new faith was offered to the captive people, and resistance to this helped other resistance.

The clergy of the old Catholic religion preached in Gaelic resistance to the English, as destroyers of the native Church and of nationality, whilst English-appointed clerics spoke in the English language to few and faint congregations. And that was the first dividing of old faith and native race against new faith and stranger. Utterly distinct and emphatic henceforward – though the names of Protestant deans following the long line of the old abbots and Catholic Church dignitaries in Christ Church and St Patrick’s Cathedrals seem to create a superficial succession, the melting in of one order to the other without sign of the violence which gives them to us so.

THE REBEL LIST

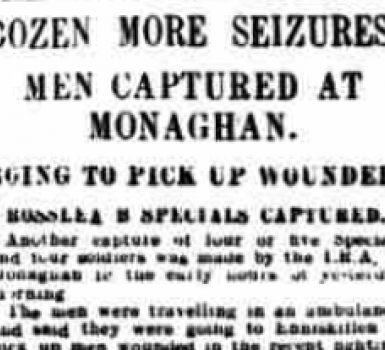

The history of Ireland, since England put her shadow on the country, has been one of physical and spiritual rebellion. Racial differences prejudiced attempts at understanding, and the weaker country definitely set her face against such attempts with each fresh aggression of the stronger.

The outstanding and simplest proof of this are the rebellions, breaking out, one to each generation, and brooding when not aflame. The list runs on from Shane O’Neill’s to the Desmond Rebellion; to Tyrone and Tyreconnel, and the insurrection of 1641. Then the Confederation of Kilkenny, and on September 15, 1643 – when the balance had been growing in favour of the Irish and the king had changed high officials to make the way clear for negotiation – that curious Anglo-Irish agreement to cease from hostilities for one year, and the indignation caused by this in England, inflamed by reports against the Irish Catholics.

England had then the unlucky King Charles, and for this chance Ireland paid int eh bloody subjugation by Cromwell. William and James again fought it out in Ireland, and we had the Siege of Limerick – the three days’ armistice, the broken treaty – all the bruised and noble-shameful flory of wars that were not for Ireland as Ireland.

STRUGGLE UNCEASING

Always a wild story; and when the noise of martial conflict died down, it was to give the ears the sobs of despair….. are we to have peace? – begin a better era? God grant it.

Yes, and a wretched story sometimes. The growth of the Irish Parliament; and in national affairs from the mid-eighteenth century a certain amount of corruption. The small band of true patriots, such as have always been found in Ireland, fighting for small reform after small reform, keeping on though things became apparently hopeless, it would seem, as the struggle between the English and Irish Parliaments became acute.

As for Irish trade, there is the statement from Pitt to the Duke of Rutland some time in the seventeen-eighties, “that the line to which my mind at present inclines is to give Ireland almost unlimited communication and commercial advantages, if we can receive in turn strong security that her strength and riches will be to our benefit.”

But the trade concessions he drew up had a lat clause giving “excess profits” (as might be said in these days) to the support of the British navy. That finished the hope of Irish trade expansion.

WEARYING THOUGHTS

After that and since, the violent fruition of national resentment. The time of the United Irishmen, suppressed but desperate; the growing hope in Ireland of seeing England under France’s heel. The bitter anguish of 1798 – Lord Edward Fitzgerald, Wolfe Tone, and the rest.

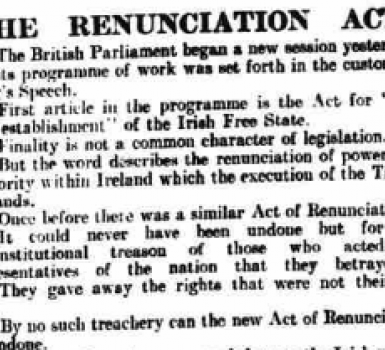

Then the Irish Union of 1801 – a new chapter an unwanted one. A couple of years later another rising, Emmet’s. And from Emmet’s to our own we seem to know within ourselves the insurgents of each generation – the Fenians, the followers of Parnell, and Sinn Fein, the movement from thirty years back, the blazing forth of 1916, and the continued resistance of our day.

And the attitude of England to Ireland all along, when England as a nation deals with captive Ireland. Subterfuge and deception – is it a wonder that doubt is obstinate? That men and women, and even ungrown children, hesitate and argue and take slow reason to sift out the possibilities of our new peace terms?

The truth is that Dublin and Ireland to-day are almost dazed; they hope for the new white era, but the passing of the centuries has taught our people to be slow in joyousness.