Trade Boycott Causes Unionist Quandary

07 March 1921

Irish Independent, 7 March 1921

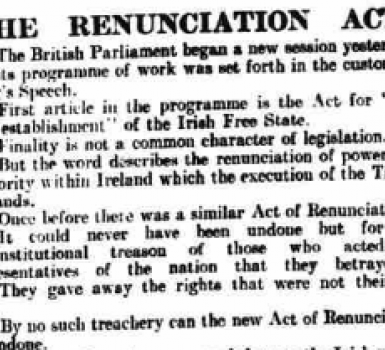

When the Government of Ireland Act was passed in December 1920, many Unionists believed that the creation of the Northern Ireland parliament would lead to increased prosperity for the six counties. This article from the Irish Independent was sceptical about the economic benefits of partition, pointing out that businesses across Belfast were suffering as a result of the trade boycott ordered by Dáil Éireann in 1920. The writer suggested that politicians were giving no thought to economic realities that would impact Protestant and Unionist businesses as much as Catholic ones. The only support the Unionist politicians had for its plans, the article claimed, was among Protestant shipyard workers who, the writer claimed, saw partition as an excuse to drive out Catholics from the six counties.

Trade Boycott and its Effects: Unionist Quandary; Results of the Pogrom Policy

If there is one centre in the new Ulster where one might expect to meet with some indications of genuine pride and deep-rooted interest in the Partition Parliament it is Belfast.

As the seat of Government for the so-called homogeneous counties, Belfast should, if the Lloyd Georgian Two-Nations theory is correct, attract to itself the industry, trade, and commerce of the counties which it governs. Consequently the stranger visiting Belfast at the present time might well be forgiven if he expected to find its merchant princes ‘swelling visibly’ in sweet satisfaction at the golden prospect in store under the new regime.

The truth is that the Orange merchants of Belfast, far from regarding the new Parliament as marking a dawn of an unprecedented wave of prosperity for themselves and their city, are appalled at the possibilities of the rest of Ireland’s commercial strangle-hold, which even today is choking Belfast’s commercial life. The paralysis of trade and industry everywhere in Belfast is causing bewilderment and panic among the business population.

The Political Bosses: Thirst for Power & Place

For the moment the political future of the six counties seems to have been entirely forgotten, save by the professional politicians and place-seekers. The Belfast of the commercial and industrial classes was never in such straits. These classes are dismayed at the prospects of a further tightening of the boycott weapon; they see in the setting up of the Parliament the completion of the city’s isolation from its natural markets in the Ireland from which they have cut themselves asunder.

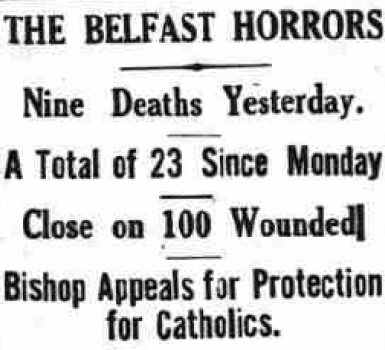

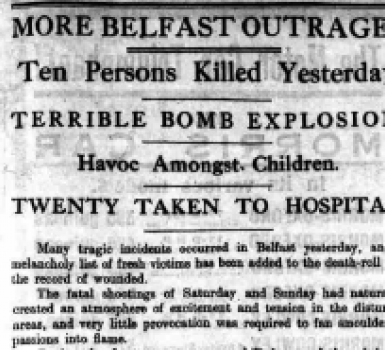

So it is that, while preparations in the ranks of the politicians are proceeding apace, outwardly an ill-concealed apathy and indifference are illustrative of the general attitude. There is an atmosphere of make-belief and unreality about the whole proposals which would by now have led to open denunciation were it not for the power and influence of the political clique. Probably in no city in Europe are the destinies of the people more completely in the hands of the politicians – all sections of the Unionist population, from those business men who influences the pogrom against Catholics last August, to the shipyard workers who enforced it, are equally obedient to the sway of the political bosses, whose dictates they but carry out. The politicians have in the setting up of the Ulster Parliament opportunities to satisfy an insatiable thirst for power and place, and, backed up by the motley army of place-hunters, they are determined to bring the Parliament into existence.

Shipyard Workers

The only vocal element in Belfast outside of the politicians is to be found among the 50,000 shipyard workers. All the ignorant prejudices and bitter religious animosities of the Ulster Orange cult are concentrated here. Whatever problem there may be in Ulster, from the point of view of an all-Ireland Parliament, it is really to be found among these workers, who are always ready to expound the theory of homogeneous Ulster, so dear to Mr Lloyd George, by driving their Catholic fellow-workers into the furnaces at Queen’s Island, or doing them to death on the streets with iron bolts and nuts.

It is not to be wondered at that on this occasion the shipyard workers are, as of old, ranged on the side of the political bosses, and see in the setting up of the Parliament the final confusion of the ‘Papishes’ and success to their inspiring war-cry, ‘To H[ell] with the Pope’.