Carson’s Farewell to Ulster

06 May 2021

Professor John Horne, Fellow Emeritus in History, Trinity College Dublin.

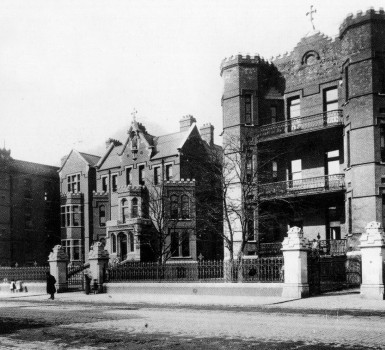

We all know the statue. Aloft in front of Stormont, Sir Edward Carson gestures defiance. No surprise there. The monument was funded, as it says on the plinth, ‘By the loyalists of Ulster as an expression of their love and admiration for its subject.’ Forty thousand attended its inauguration in November 1932, the year the Stormont parliament building behind it was completed. Carson was there to receive the tribute of the people he had mobilised against Irish nationalism twenty years earlier. Yet the occasion when he left Ulster politics a decade before that, in 1921, tells a different, less triumphalist story. Then, Carson had an almost subliminal message – a moment of truth.

‘You Have Got Your Own Parliament’

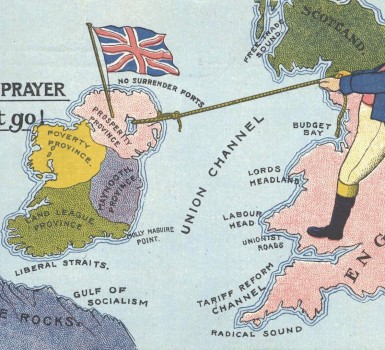

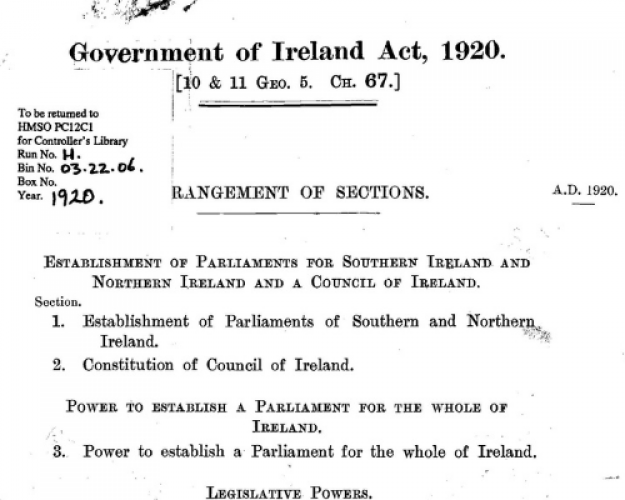

First, the context. In 1920, London ‘settled’ Home Rule with two devolved parliaments: one for a six-county Northern Ireland, the other for a twenty-six county Southern Ireland. In theory, provision for an all-Ireland council allowed for future unity, should North and South agree.

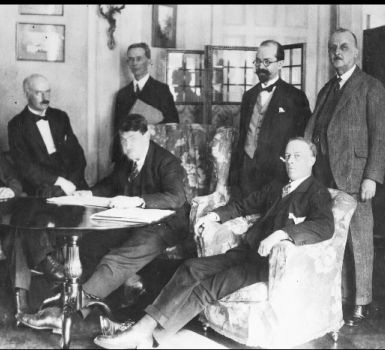

Given the political realities of the time, this was unlikely, to say the least. The settlement confirmed partition, creating an assembly in the North whose reduction to six counties (from the nine originally envisaged) ensured a built-in Unionist majority. War with Britain continued in the South. But ahead of the opening of the Northern parliament in June 1921, Ulster Unionists met to elect Sir James Craig as Carson’s successor when the latter retired after eleven years as leader of Northern Unionism.

Now the occasion. This was a meeting of the Ulster Unionist Council on 4 February 1921. The overriding feelings were hope and gratitude. Craig foresaw a new start for the ‘province of Ulster.’ He wanted to ‘take a great sponge and clean the slate and say: ‘All that lies behind is past and forgotten.’ This, and the ‘Ulster parliament’ that allowed it, he saw as Carson’s ‘heritage’.

By contrast, an emotional Carson was bitter-sweet. ‘You have got your own parliament,’ he said (addressing his colleagues as ‘you’ not ‘we’), and ‘if there are advantages’ these included not being a pawn in the politics of others. But the note of doubt (‘if there are advantages’), at such a moment of triumph, jarred.

For Carson was born and educated in Dublin, a Southern Unionist who had introduced hurling to Trinity College and spoke with a Southern accent. He lived in London, not Belfast. The divided Home Rule introduced by the 1920 Act, and thus the ‘Ulster parliament’, marked the defeat of his political life – his deepest allegiance being to a single Ireland within the union. For Carson, this was an end, not a beginning. With the Anglo-Irish Treaty and the founding of the Irish Free State ten months later, he drank the cup of betrayal to the bitter dregs.

Moment of Truth

And so to the moment of truth. Carson warned his fellow Unionists:

If you get a majority at the elections […] you will no longer be an organization for a party. You will be a parliament for a whole community. We used to say that we could not trust an Irish Parliament in Dublin to do justice to the Protestant minority. Let us take care that that reproach can no longer be made against your Parliament, and from the outset let them see that the Catholic minority have nothing to fear from a Protestant majority.

The paradox was that resisting Home Rule in defence of the union in Ulster redefined Irish Unionism as a territorial enclave in the north-east, with its own religious and political minority. Carson, who had feared just that outcome for Southern Unionists, was sharply attuned to it. Not so his Northern colleagues. Craig ignored it. Indeed, contradicting his point about a ‘clean slate,’ Craig insisted that ‘the policy of the future will be the future of the past, and that will be no surrender to the destroying, disintegrating forces of the country’ – by which he meant Irish Nationalism.

But Carson’s warning was prophetic; a new minority had been created on whose recognition and status the whole undertaking depended. Even Carson defined the minority in religious terms (Catholic, not Nationalist), which made the matter one of religious toleration rather than political difference. Still, he put his finger on the issue that was emerging across much of central and eastern Europe at the time, as new nation states were founded in the wake of the First World War.

All of these new nation states had ethnic (and often religious) minorities with their own political aspirations, whose mere existence challenged the majority’s understanding of the nation and state as unitary. Hence, the League of Nations called for the recognition of minority rights and sought to protect minorities during the interwar period. Britain played a key role in this. But it never thought to apply it to its own new province.

Carson’s Final Caution

A century later, we can sense the irony in the grand sweep from Carson’s statue to the Stormont building. Brand new in 1932, though seeming to have been there forever, the neo-classical structure housed Craig’s ‘Ulster parliament.’ But the Carson who faces south from his plinth, and who seemed to embody a secure northern future, surely looks over the border to his native Dublin and a single Ireland within the union that had forever gone.

Meanwhile, the failure to heed his warning meant that a mere half-century later, the ‘Ulster parliament’ was dead. That same irony makes it all the more worthwhile to reflect on Carson’s moment of truth. What replaced the defunct Stormont, after thirty years of conflict, has obeyed his injunction not to ignore the minority.

At a time when the border is once more politically sensitive, when talk abounds of ‘taking back control’ or ‘uniting Ireland’, and when it is not even clear who will be the ‘majority’ in the future, Carson’s final caution deserves, perhaps, to become more than a pious hope: ‘Take care that we win all that is best among those who have been opposed to us in the past’.