Standing Guard over Ireland’s Unity? Partition and St Patrick

06 October 2021

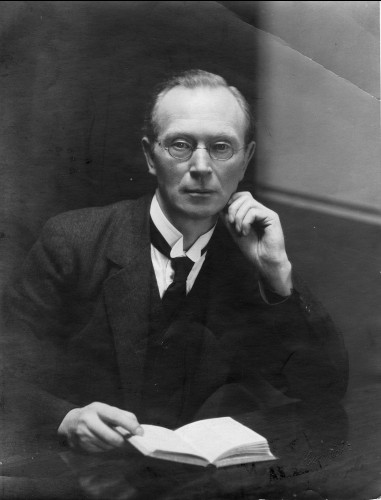

It would be shocking if the fallout of such a pivotal event as partition was not detectable within that immense body of historical writing concerned with Ireland’s national apostle, Saint Patrick, especially since Eóin MacNeill so actively bridged the country’s political and academic spheres.

MacNeill is probably known to many readers owing to the decisive role that he played, as leader of the Irish Volunteers, in the development of the 1916 Rising. But his interest in Saint Patrick was arguably unparalleled amongst his peers (one historian, Tarlach Ó Raifeartaigh, dubbed MacNeill the ‘prince of Patrician studies’). MacNeill’s article, ‘The fifteenth centenary of St. Patrick: a suggested form of commemoration’, is a case in point. It appeared in the Jesuit journal Studies: an Irish quarterly review in 1924; so roughly seven years before the anniversary – celebrated by the Catholic and Protestant Churches – of the year (432) in which Patrick is thought to have commenced his mission in Ireland.

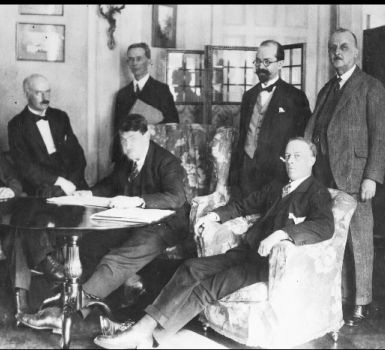

Importantly, 1924 saw the constitution of the Boundary Commission; a body upon which MacNeill sat as the representative of the Free State, resigning before it delivered its final report. Revd John Ryan, MacNeill’s successor as Professor of Early Irish History at U.C.D., recalled MacNeill’s ‘disgust at the very idea of such a Commission – it was an outrage... against civilisation to draw a dividing line across Ireland’.

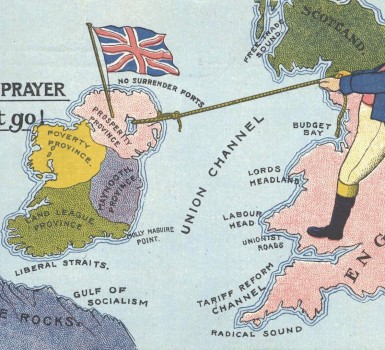

The point here is that if you read MacNeill’s article, it quickly becomes clear that his abhorrence of partition was not merely a product of heartfelt nationalism, as it is easy to assume. It was also rooted in his intense, Roman Catholic faith: a consequence of his profound reverence for Ireland’s, and more specifically, his native Ulster’s Christian heritage (he hailed from Glenarm, Co. Antrim, an area steeped in Patrician lore and from which Mt. Slemish can be viewed). ‘Saint Patrick’s memory,’ as MacNeill argued, ‘stands guard over Ireland’s unity. Armagh, Downpatrick, Sliabh Mis, nothing can separate them from “the apostle of Ireland entire”’. So for MacNeill, partition was essentially heretical: it not only ruptured the island’s geographical and political unity, but, crucially, it wounded that deeper, spiritual unity forged by Patrick’s introduction of Christianity to Ireland, even if it could never fully extinguish it. For MacNeill, Patrick bound Ulster to the rest of the island and vice versa. Patrick’s legacy thus trumped partition.

Yet MacNeill struggled, clearly, to reconcile himself to the fact that one part of the island, not least the fledging Free State, with its innate Roman Catholic ethos, was now cordoned-off from many of the most sacred Patrician shrines (just as it was undoubtedly an affront to loyalist sensitivities that partition conceded such a hallowed site, that of Battle of the Boyne, to the South). MacNeill’s thinking was not unique in this respect. Preaching in Armagh Cathedral on St. Patrick’s Day, 1938 (the year that saw the unveiling of the statue of Patrick on Slieve Patrick near Slemish), MacNeill’s lifelong friend, Cardinal Joseph MacRory, remarked:

'It was strange and sad that the places most intimately connected with St. Patrick were now cut off from their country by partition. Slemish…where…the saint made his novitiate; Saul where he began his missionary work and where he also breathed his last; Armagh where he founded the Primatial See. Downpatrick where repose his mortal remains. They hoped and prayed that the unnatural and unjust separation would soon be brought to an end and that Irishmen of all creeds would learn to live together…without any artificial boundaries.'

MacNeill’s article also reflects fascination with Patrick as a figure who had a knack for reconciling differences upon the island. MacNeill was keen to highlight how the Saint successfully ‘worked for the unity of the Irish people not only in religion but in civil and social life’. It is natural, given Ireland’s turbulent history, particularly during the early 1920s, that individuals should have found themselves comforted by the vision of a seemingly harmonious, peaceful Ireland generated by the former slave’s skilful blending of Christianity with the island’s pagan learning, laws, and customs. Against the backdrop of partition and ensuring civil war Stephen Gwynn (Protestant home ruler, writer, and father of the Jesuit historian Aubrey Gwynn) published The History of Ireland (1923). ‘Patrick’s conciliation of the learned men and poets was wisdom,’ Gwynn argued: ‘…He endeavoured to develop what was best in their own institutions, avoiding all unnecessary conflict’.

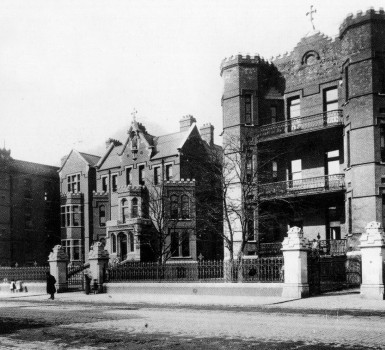

And there is a sense in which Patrick’s memory has continued, as MacNeill claimed, to nudge Ireland’s inhabitants towards reconciliation. The much-anticipated ‘Patrician Year’, the fifteenth centenary of the Saint’s death, arrived in 1961. People wore ‘Patrician badges’ and tens of thousands attended open-air masses at Slemish and Saul and at Croke Park Stadium. But it is a lesser-known fact of Irish history that the opening ceremony of the ‘Year’, a Pontifical Mass in Armagh Cathedral, occasioned the first visit of an Irish President, Eamon de Valera, to Northern Ireland. This was a development which almost certainly helped pave the way for Taoiseach Seán Lemass’ more well-known, symbolic trip north in January 1965. There has long been a suspicion, moreover, that Patrick’s choice of ecclesiastical capital, Armagh, might have been put to better use in terms of fostering reconciliation in Northern Ireland. After a meeting with SDLP member, John Hume, in Derry/Londonderry in July 1973, a representative of the Northern Ireland Office reported that Hume (formerly a seminarian at St. Patrick’s College, Maynooth) had argued that the ‘Cathedral City’, rather than Stormont, ‘would be a much better place for the inaugural meeting’ of the power-sharing Assembly proposed in the British government's white paper Northern Ireland Constitutional Proposals. ‘The Unionists had suggested it in 1920,’ Hume explained ‘and the Prelates of the two main Churches could bless its deliberations’.

Yet somewhat like the island’s constitutional history, so partition has long been a cause of conflict amongst scholars interested in Patrick. In 1942 Thomas Francis O'Rahilly contended that our beloved Saint was actually an amalgamation of two missionaries: Bishop Palladius, apparently known as Patricius, who operated around the south-east of the island; and Patrick the Briton, author of the Confession, a work in which, significantly, neither Rome nor the Pope is mentioned and who continued his predecessor’s work in Connaught and broke new ground in Ulster.

O’Rahilly’s theory was not completely new, of course: the idea that there were two Patricks’ has been around (as MacNeill once pointed out) since the mid-seventh-century. O’Rahilly’s division was rendered all the more controversial, however, because, crucially, it seemed to reflect or play-off partition: you now had a Catholic Patrick – dispatched to the island by the Pope – that operated mostly in the South, and a British one, who seemed to have operated a lot in Ulster, and who did so, seemingly, independently of Rome. It was, in a way, the ‘two nations’ theory of Irish history, but applied to Patrick. My Ph.D. supervisor, Owen Dudley Edwards, has frequently regaled me with the anecdote (one that I would dearly love to corroborate) about how, after O’Rahilly aired his theory of the ‘Two Patricks’ at Trinity College Dublin, the university’s Provost, Ernest Alton, who chaired the lecture, exclaimed something along the lines of, 'Wonderful! Now the Catholics can have one and the Protestants can have one!’

Others were equally impressed: the ‘most brilliant paper ever written on a point of Irish history’ as one historian (Gerard Murphy) described O’Rahilly’s theory. But scholars of a Catholic nationalist persuasion were, to put it mildly, rather less upbeat. For Revd John Ryan – an ardent nationalist – O’Rahilly’s partition of Patrick was just as illegitimate as Britain’s partition of Ireland. The theory of the ‘Two Patricks’ may have solved some long-running causes of scholarly conflict, Ryan conceded, but it did so only ‘by the crude expedient of cutting the missionary in two, a procedure hardly justified by the historical situation’. Ryan’s allusion to the (as he saw it) unnecessary and clumsy division of the island is, I think, not exactly subtle here.

O’Rahilly’s theory certainly failed to resolve that now age-old debate as to whether the faith that Patrick preached essentially displayed all the characteristics of Protestantism - the very awkward fact that the Saint lived well over a thousand years before the Reformation has never really troubled proponents of this view - or whether, as the likes of MacNeill and Ryan maintained, Patrick was devoted to the Pope. Ian Paisley’s sermon, ‘Patrick was not a Roman Catholic’ (easily available on the Free Presbyterian Church’s website), is a prime example of the former perspective. Here, Paisley insisted that there was no trace of Catholic dogma in Patrick’s teachings and that the Saint endeavoured as far as possible to partition his fledgling Celtic Church off from the influence of Rome. Arguably, Paisley’s sermon is worth having a listen to just to hear his historical theory that it was actually the Pope (Adrian IV) ‘who brought the British into Ireland’ in the first place, and who did so, according to the former leader of the DUP, in order to force the fiercely independent, Bible-based Church founded by Patrick to tow a very superstitious, authoritarian Vatican line. So if Paisley is to be believed, responsibility for partition may ultimately lie with the Vatican, not Westminster…

Scholars are increasingly keen to understand the manifold and often subtle ways that the creation of Northern Ireland impacted upon people’s lives and ways of thinking. Using Saint Patrick as a sort of vehicle to explore Irish mind-sets is but a a novel, if incisive, and – dare I say it – rather fun way of doing so. For Patrick is, as MacNeill perceived, a sort of constant within Irish thought: spanning centuries and transcending political and sectarian allegiances – even if he has caused a few fallings out over the years.

Dr Tommy Dolan, University of York