Ending the Scrap: From War of Independence to the Treaty

06 December 2021

On 11 July 1921, ‘the scrap’, as IRA veterans were wont to call it, paused, it seemed momentarily. The message from General Richard Mulcahy, Chief of Staff of the Irish Republican Army, read: ‘In view of the conversations now being entered into by our Government with the Government of Great Britain, and in pursuance of mutual conversations, active operations by our forces will be suspended as from noon, Monday, 11 July.’ The Truce was greeted with wild celebrations in parts of the country - bonfires, marching bands and good-natured banter between IRA Volunteers and their belligerents, notably the Black and Tans. Dublin was reported as calm rather than the scene of high excitement although as John Dorney has pointed out, the most immediate visible sign of the truce was the withdrawal of police and military cars and lorries from the streets.

Many names have been given to the conflict commonly dated from 21 January 1919 to 11 July 1921: the Anglo-Irish War, the Tan War, the War of Independence, the War for Independence, the Troubles, the Scrap. But there was much variation beneath the surface. It is important to note the patchy geographic nature of the hostilities, particularly in the early stages. Cork was an especially active part of the country; other counties, like Clare or Tipperary, were hotspots in the early phases, but declined somewhat over the second half of the conflict. Dublin, like Cork, was a perennial flashpoint - the highest concentration of British troops and the organisational nucleus of IRA GHQ meant that it provided ample scope for confrontation.

But other counties were more quiescent early on, or sparked into activity at later stages, helped along the way by the radicalising effects of British policy, especially after the winter of 1920, and by the travelling organisers sent out by IRA GHQ to bring local units up to scratch. Much depended on ‘local conditions’, as the phrase went. The numbers in the local IRA units; their appetite for action; their capacity to secure weapons - this drove a high proportion of the early IRA actions. IRA actions varied, from attacks on RIC barracks, to the flying column operations of Kilmichael or Rineen, to gunbattles on the streets of Dublin, to the targeted assassination of RIC members, to the sensational assassinations of Dublin Castle intelligence agents on Bloody Sunday 1920.

Moreover, levels of activity fluctuated over the period of the conflict. By the time of the Truce, what had been previously calm counties in the midlands and especially the west of Ireland were becoming more active, while after the disastrous attack on the Custom House in May 1921, the IRA in Dublin were in a precarious state. Even as the killings in the rest of the country wound down, violence in Belfast and across Northern Ireland racheted up again, with 22 people killed in inter-communal violence in the days leading up to the Truce.

Faced with an effective guerrilla campaign with a high level of support in the local population, the British government had to respond. But the question of which arm of the British state should take the lead in countering the IRA campaign was a political, and politicised, decision. The term ‘war’ was not favoured by the British government; it was ‘civil disorder’, a ‘murder gang terrorising’ the population. It was a police matter, to be dealt with by the police, even a highly militarised police force such as the RIC. But it couldn’t be dealt with by ordinary policing. It required massive reinforcements (the Black and Tans and Auxiliaries), it required the suspension of habeas corpus, it required internment camps, it required special legislation, and it required martial law, gradually extending across the whole of the country.

The reprisals policy, tolerated and sanctioned at official level, gives us another window into how the War of Independence progressed. Collective punishment of the civilian population, including economic destruction of creameries and co-operatives, formed part of the British state response. This was not just some hotheads running amok, enraged by the deaths of their comrades (although that may have been part of it). It was also a deliberate strategy to make clear to civilians what the price was of silence and of safe houses. As conditions deteriorated across Ireland in the summer of 1920, ‘normal’ justice ceased to function, along with the capacity of the British judicial system to apprehend and convict IRA members.

Shooting ‘known Sinn Féiners’, as the phrase went, thus often ran alongside sacking and burning a town. This cycle of violence - attack on Crown forces, followed by shootings and burnings - was a recurrent feature of the War of Independence, from Tuam to Balbriggan to Cork City. Reprisals, however, only worked up to a point. In a world of increasing connectivity, with active publicity/propaganda campaigns being carried out by the republican administration and foreign correspondents aplenty visiting Ireland, the brutality of reprisals was v politically counter-productive and had a major impact on British public opposition to the campaign in Ireland, as well as on international opinion. It also cost a lot - the conflict in Ireland tied up 80,000 troops and was estimated to cost the British £20m a year.

Across the conflict, even as the pace or density of violence varied, and as old opponents retired and new ones arrived, some problems loomed on the horizon. The degree to which the military campaign on the republican side was joined up with the political one was one potential issue. The relationship of Sinn Féin with the IRA, and with the IRB within that, was not altogether straightforward. The Irish Republican Brotherhood was a revolutionary secret society which had been instrumental in the establishment of the Irish Volunteers or Irish Republican Army. Some senior figures, like Eamon de Valera and Cathal Brugha, believed that the decisive emergence of the Irish Republican Army after 1918 meant that there was no longer any need for a secret society like the IRB. Others, like Michael Collins, continued their IRB membership, and so the latter organisation operated as a secret society within the IRA, complicating notions of authority. Sinn Féin, as the party whose TDS theoretically constituted the Irish Republic, was another rival source of legitimacy.

Certainly, there was a large overlap of personnel: many Sinn Féin TDs were IRA officers, many Cabinet members were senior IRA figures, some were also members of the IRB, and many Sinn Féin and Dáil staff were members of Cumann na mBan. However, the coincidence of the Soloheadbeg ambush, when Irish Volunteers in County Tipperary attacked a Royal Irish Constabulary accompanying a delivery of gelignite to a local quarry, killing two policemen, on the same day as the first meeting of Dáil Éireann gave the impression of cohesion and coordination where this was not always the case. The much delayed, haphazard and patchy efforts to get all IRA Volunteers to swear an oath of allegiance to the Dáil (and by extension to the principle of civil government) also speaks to this - Volunteers had already sworn an oath to the Irish Republic. It wasn’t until April 1921 that the Dáil formally accepted responsibility for the IRA campaign. Local commanders were accustomed to making their own decisions as well as sourcing their own weapons. Authority and command were thus fluid, at least partially, during the War of Independence which had important implications for conceptions of legitimacy in the fraught period after January 1922.

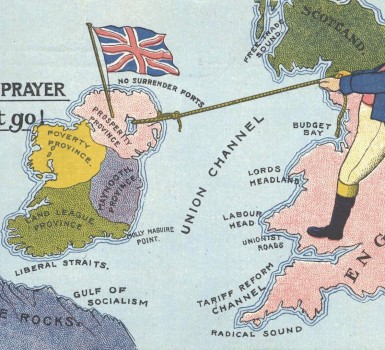

Another important factor during the War of Independence was the very different experience of the north-east of Ireland. As I’ve already indicated, the pattern of violence was different there: it operated to a different pace, it had a different character (much more street violence, sniper activity, riots as well as ambushes, lots of assassinations), and it had different protagonists (loyalist paramilitaries, some Ancient Order of Hibernian units and, after October 1920, the Ulster Special Constabulary). By the time the Truce was declared, Ireland had been formally partitioned by the Government of Ireland Act, and the new Northern Ireland parliament had met for the first time. But violence was nonetheless continuing: the autumn of 1921, while the Truce was notionally in place, saw renewed outbreaks of serious violence in Belfast. The differential experience of the north-east of Ireland continued to loom large as the Treaty negotiations began.

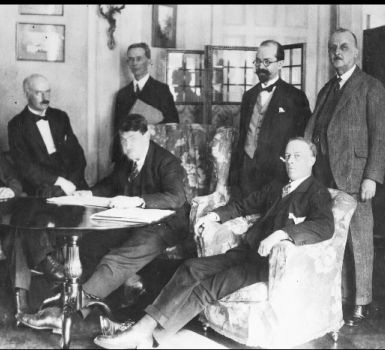

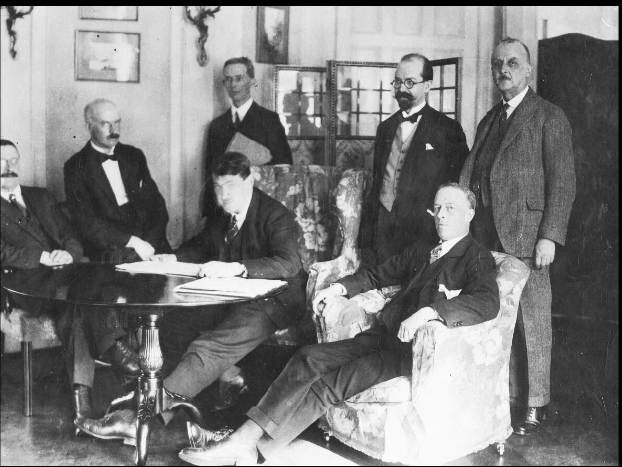

By the time the Truce was declared in July 1921, back channel negotiations had been going on for some time, between a group of hardheaded civil servants in Dublin Castle and those who were perceived as ‘moderates’ in Sinn Féin (Griffith and de Valera, principally). But moderates and pragmatists talking to each other was one thing. Reaching public agreement on a settlement was another. As the Treaty negotiations began, deep-seated potential obstacles were becoming clear. Chief among these was the degree of compromise already implicitly conceded by the decision to enter into negotiations. Short of forcing a British withdrawal (militarily impossible), a process of political negotiation, resulting in some form of compromise, was the endgame. The letter inviting de Valera to send a delegation to London contained the careful phrase: ‘to ascertain how the association of Ireland with the community of nations known as the British Empire may best be reconciled with Irish national aspirations.’ How, not whether. But this was not necessarily the message being given to IRA officers certain that ‘one more push’ would secure the victory.

The Truce, registered as a military agreement with the League of Nations, was not the unconditional surrender the British had originally demanded, or even a conditional surrender. No weapons were surrendered at all, and there were renewed efforts to import weapons during the summer of 1921, training camps established all over the country to bring the Trucileers up to scratch; all of this implying that a resumption of hostilities was imminent. And, of course, this was necessary in order to give the negotiators the strongest possible hand. The shape of a future settlement had already caused one mini-crisis within the republican movement. De Valera, while on tour in the US, mused to an American reporter that Ireland’s future relationship with Britain could be something akin to Cuba’s relationship with the United States. This provoked a flurry of outrage at home, and de Valera had to eat some humble pie in his correspondence with his Cabinet. Of course, all of this begs the question as to why, if de Valera had acknowledged as far back as February 1920, that some form of compromise short of a republic was likely, why he refused to support the Treaty agreed in December 1921. That is a question that has continued to exercise historians in the hundred years since that momentous decision.

Dr Caoimhe Nic Dháibhéid, University of Sheffield