The Road to Civil War

08 February 2022

.jpg)

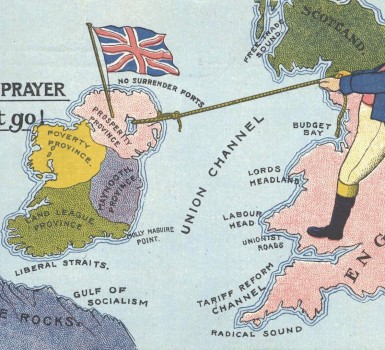

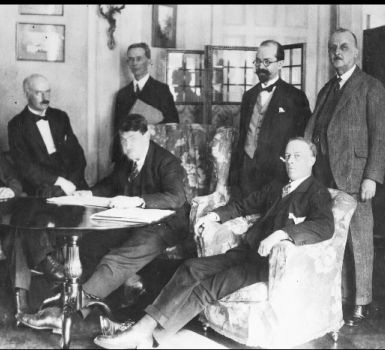

While violence had reached new levels during early 1921, it was unclear which side was ‘winning’ at the time of the Truce in July. The IRA had suffered serious setbacks in Cork, Dublin and the north west and 4,500 IRA volunteers were in jail or interned. IRA leaders Richard Mulcahy and Michael Collins would later argue that the shortage of arms and ammunition had reached critical level. There was also undoubtedly widespread war weariness.

Naturally then, the announcement of a truce was very popular with the population at large. But news that hostilities were to end came like a bolt out of the blue to many of the IRA’s local units. They had become more ruthless and effective in many areas: the nine weeks before the Truce saw over a quarter of the losses suffered by the Crown forces in the entire war. So there was confusion and some annoyance that there had been little consultation with local units about the leaderships’ decision.

But advantage was taken of the breathing space. Between the Truce and the Anglo-Irish Treaty in December the ranks of the IRA swelled dramatically. Though there was some resentment at these so-called ‘Trucileers’, the IRA leadership welcomed expansion and were pleased at the opportunity to train and re-arm. Recruits were drilled and given instruction in battle tactics, while intelligence gathering and arms procurement continued.

Despite the Truce, violence had continued. In Belfast especially, the killing was worse between July and December 1921 than anything that had gone before. What to do about the situation in the North was one worry; discipline was another. Seán Moylan later recalled that during that period some republicans ‘pushed the ordinary decent civilian aside and earned the IRA a reputation for bullying, insobriety and dishonesty that sapped public confidence.’

The news of the Treaty then came as a huge shock to most officers and volunteers. They had simply not been kept abreast of any likely compromises and many instinctively rejected the agreement.

Outside of GHQ in Dublin, whose key activists remained loyal to Collins, the pro-Treaty IRA was limited to some midland’s brigades (of which Longford had been the most active), east Clare and east Limerick in Munster and Donegal and Cavan/Monaghan in Ulster. However much of the IRA north of the new border, including those in Belfast, remained well disposed to Collins and Mulcahy. But most men followed the lead of their officers and an estimated 75% of the IRA opposed the Treaty.

These included the large and militant southern and western brigades including Cork, Kerry, Tipperary, Sligo and Mayo. However the anti-Treatyites were by no means agreed on what course to take. A few, such as Rory O’Connor and Liam Mellows, were in favour of overthrowing the new Provisional Government, while others like Tom Barry wanted an attack on British forces to reunite the republican forces. Cork’s Liam Lynch and others sought to avoid conflict.

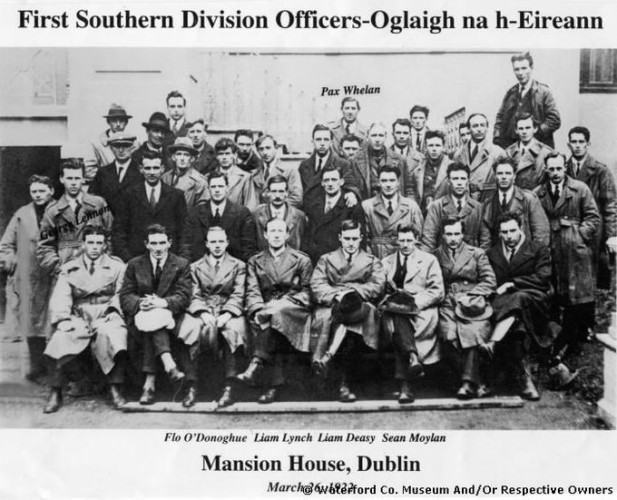

Indeed, a very significant number of men, including Frank Aiken from Armagh, opposed the Treaty but were not prepared to fight over it. Nevertheless, during the spring of 1922 there had been a series of confrontations between the rival IRA’s over control of former British military barracks in Limerick, Tipperary, Offaly and Galway. On Sunday 26 March 1922 delegates from units across Ireland met in Convention at Dublin’s Mansion House. The significance of the event was twofold.

Firstly, they met in defiance of an order prohibiting the convention by Arthur Griffith, President of the provisional government. That directive was supported by the Minister for Defence and IRA chief of staff Richard Mulcahy, who had warned that ‘any officer participating in it (the convention) will thereby sever his connection with the IRA’. Many delegates suspected that forces loyal to the provisional government would try to arrest them and so came armed and prepared for a fight.

The convention formalized what was already obvious; that the IRA had split over the Treaty and the majority of its men were not under the control of the new government. The convention organisers asserted that the IRA, as a volunteer army, organised on a democratic basis, had a right to meet to discuss the Treaty. As Rory O’Connor argued at a press conference in Dublin on March 22, the IRA was ‘not a mercenary army … the army had rights as citizens as well as soldiers’.

Moreover the organisation did not ‘belong to any political party’ and owed its allegiance only to the republic declared at Easter 1916. Facing questioning from reporters about whether the IRA would prevent a general election taking place O’Connor answered that it would be ‘in its power’ to do so. Asked then if this meant a military dictatorship he replied ‘you can take it that way if you like…’. O’Connor later claimed that his views had been misrepresented but mention of dictatorship spread alarm among the public. The interview also annoyed many of his Anti-Treaty comrades as O’Connor did not have the authority to speak for them.

Nevertheless, the position of the officers at the convention was that the Treaty had been signed under duress and that the threat of British military action (‘immediate and terrible war’) made a free election impossible. The IRA would not therefore be bound by either the new government or the electorate. Despite the split, many of those at the convention were not eager to fight their former comrades, a situation further complicated by the fact that both sides of the IRA were also now cooperating in secret operations north of the border.

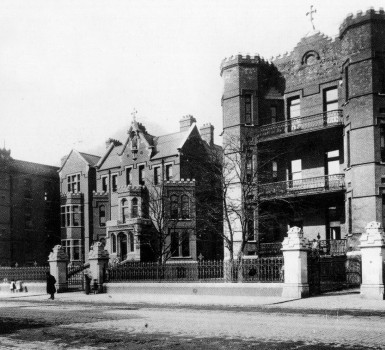

But a few weeks later, on the night of 13 April, armed men took over several buildings in Dublin city centre. The Four Courts became the headquarters of the most uncompromising IRA leaders, including O’Connor, Mellows and Ernie O’Malley. The existence of this ‘Four Courts garrison’ was a public challenge to the authority of the government. In carrying out this action, taken without consultation with other leading officers such as Liam Lynch, a section of the IRA leadership had made confrontation with either the Dublin or British governments (whose forces not yet left the 26 counties) much more likely.

Dr Brian Hanley