The Ulster Special Constabulary

02 February 2022

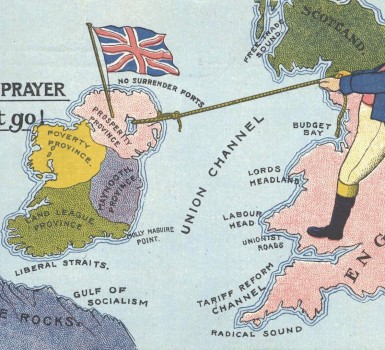

The Ulster Special Constabulary’s (known as the Specials) origins lie in the Ulster Volunteer Force, formed in 1912 in opposition to the third home rule bill. Apart from military service, it was inactive during the First World War, but ready to act if required. In May 1918 it numbered c50,000.

From late 1919 levels of tension rose sharply in the northeast, mainly due to the prospect of partition. Nationalist gains in local government elections (January/June 1920) caused unionist unease. The likelihood of conflict was heightened by the region’s history of sectarian violence, deepening recession and, above all, the Anglo-Irish War/War of Independence (1919-1921) which spilt over into Ulster. The IRA murder in Cork of an RIC officer from Banbridge (17 July 20) helped cause the expulsion of c5,500 Catholics from Belfast shipyards, and the Dáil to instigate a retaliatory boycott of goods from the northeast. The murder of another RIC officer (22 August 1920) in Lisburn resulted in Catholics being expelled from the town.

Meanwhile, more militant elements within the Unionist Party expressed growing concern over security provision – fearing the IRA campaign would spread to the region, doubting Dublin Castle had the will or capacity to preserve order and concerned that British troops based in the north would be transferred elsewhere in Ireland. From May 1920, UVF units mushroomed. In June, unionist leaders decided to revive the force, and pressed Westminster to grant it official recognition. Some in Dublin Castle were strongly opposed; Sir John Anderson, joint Under Secretary and effective leader of the administration, commented: ‘you cannot recognize one of the contending parties… in a faction fight’. Sir Nevil Macready, General Officer Commanding-in-Chief of the British forces, resisted the ‘raising of Carson’s army from the grave.’ Reluctantly, Lloyd George, the prime minister, acceded to Unionist pressure (8 September 1920), mainly because of the need to deploy more troops in the South. The force was hastily recruited and inadequately trained. These months also witnessed the ‘birth of the Northern IRA’, when Dublin HQ reorganized its units into divisions.

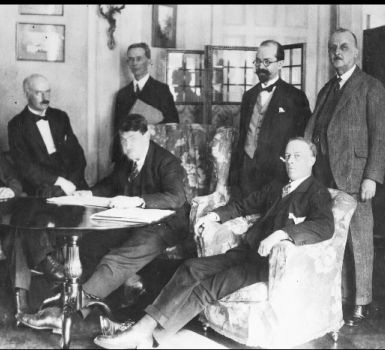

In 1921, political excitement in NI was fuelled by parliamentary elections (24 May); the minority adopted a policy of abstention, and nationalist controlled public bodies pledged allegiance to Dáil Éireann. George V’s speech, when opening the new parliament (22 June), contributed to the signing of the Truce (11 July), which again heightened tensions: the USC was suspended, and the IRA granted legal status. By October IRA membership had doubled, and its northern Officer Commanding claimed that ‘practically all’ the minority supported it. By then Unionists were feeling isolated, vulnerable, fearful of a full-scale IRA campaign, and distrustful of Westminster’s talks with Sinn Féin. Levels of violence rose; there were 165 deaths in the six counties (July 1920-November 1921), and membership of protestant paramilitaries soared to 21,000 (by November 1921). The Treaty (6 December 1921) aggravated the situation further. Its Article 12 (Boundary Commission clause) terrified unionists, and raised nationalist hopes of unity.

In early 1922 continuing political uncertainty fomented sectarian tension. Decisive was the deterioration in North/South relations. Talks between Craig and Collins proved fruitless. Collins’ intervention was increasingly determined by his concern to prevent civil war in the South over the Treaty. He covertly sponsored the IRA’s campaign to make NI ungovernable and attain unity. Levels of violence escalated. Craig responded by mobilizing the USC (January 1922), reinforcing it, and introducing the Special Powers Act (7 April 1922). The level of disorder peaked in May, when North and South were virtually ‘openly at war’ and NI in a state of civil war; 600 violent incidents were recorded that month. Some historians (e.g. Kieran Glennon) regard Protestant violence then as being ‘less reactive’ than before, and ‘more aimed at suppressing Nationalism entirely.’ The precise role of the Specials in this is unclear. But Basil Brooke (Fermanagh) described the ‘A’ Specials as a ‘wild crowd’, and General A St Q Ricardo (Tyrone) lamented ‘B’ Special indiscipline, and claimed that the force kept ‘sectarian death lists’, carried out reprisals and destroyed nationalist property. Glennon, however, attributes some of the worst reprisals (McMahon murders, Arnon Steet killings) to an RIC ‘murder gang’ formed in September 1920.

The level of violence subsided in June mainly because of Craig’s security measures (there were then 32,000 Specials; 728 almost exclusively ‘republican suspects’ were interned), and civil war in the South (28 June 1922) after which the IRA ceased operations in the northeast.

To nationalists the USC were the ‘dregs of the Orange lodges’, and spearheaded an anti Catholic ‘pogrom’ (the term originated in 1880s Russia, and has connotations of organized, state-sanctioned violence against a defenceless minority, provoking a diaspora). Rather than use its emergency powers to discipline militant loyalists, Craig’s government had encouraged paramilitary members to join the Specials as a means of ‘taming’ them. During the ‘troubles’ (1920-22) Northern nationalists suffered disproportionately. In Belfast 498 people died, 56% of them Catholic though they comprised just 24% of the city’s population. In NI overall 644 died; 57% of them were Catholic, though the state was two-thirds Protestant.

To unionists, the USC was a dedicated, heroic force which had frustrated republicans intent on ‘arson and murder’ at heavy cost (54 Specials died). They regarded the violence as either perpetrated, or provoked, by the IRA, and claimed that any reprisals the Specials carried out were unauthorized by government. Certainly Craig was anxious to preserve Unionist discipline fearing that otherwise, Westminster would ‘wash its hands of’ the north.

Craig’s government was reliant on the USC as its peace-keeping force: British troops played a minor role as Westminster feared re-igniting the Anglo-Irish War/War of Independence; the RIC was demoralized, under-strength and being disbanded (31 May 1922), and the RUC not operative until 1 June. But the outrages committed by elements within the USC and others left a permanent legacy. They powerfully reinforced minority alienation from the NI state. As a consequence of Nationalists’ failure to engage with it during its most formative years (1921-25) they were, Robert Lynch states, ‘robbed… of any say in the future shape of its institutions or political culture’ (its police forces, educational system, the local government reform). As for Unionists, this period reinforced their siege mentality which persisted long after the siege had lifted; hence the USC was the vital backbone of the security forces until March 1970 and the Special Powers Act remained law until 1978. Clearly ‘problems were being stored up for the future’ (Bryan Follis).

Dr Brian Barton