Class Matters: Aspects of the First Northern Ireland Election

24 May 2021

Professor Graham Walker, School of History, Anthropology, Philosophy and Politics, Queen’s University Belfast.

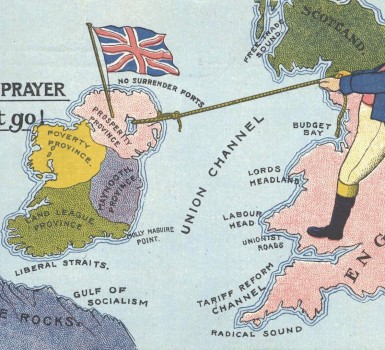

The Northern Ireland election of 24 May 1921 is notable for a number of reasons. It was the first election held in the six-county political entity created by the Government of Ireland Act 1920. As such, it was the first election in a part of the United Kingdom (UK) to receive devolution. In addition, it was the first election in the history of the UK to be conducted under a Proportional Representation system, in this case the single transferable vote.

The election took place in an atmosphere of communal tension, following outbreaks of serious sectarian violence in Belfast, Derry, Lisburn and elsewhere from the summer of 1920, and in the context of the state of war in the rest of Ireland between the British armed forces and the Irish Republican Army (IRA).

Unionist Electoral Priorities

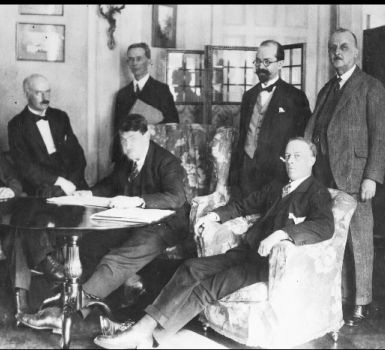

The outcome of the election was a resounding victory for the Ulster Unionist Party, led by James Craig, which secured 40 out of 52 seats in the new House of Commons. The other 12 were split evenly between Sinn Féin and the remnant of the Irish Parliamentary Party in the North whose figurehead was Joe Devlin. The result strengthened the Unionist Party’s hand in their mission to get Northern Ireland up and running and to put in place the provisions of the 1920 Act relating to their territory, notwithstanding the continuing uncertainties regarding the constitutional future of the rest of Ireland.

The emphatic Unionist triumph should not, however, prevent us taking note of the anxieties affecting the party prior to the poll. And it is by scrutinising these anxieties that we can acquire an insight into how Unionists approached their governing responsibilities and orchestrated the political life of the devolved unit thereafter.

The Unionist Party put a premium on the communal unity of their Protestant support base above all else. It was this that had been the obstacle to Irish Home Rule before the First World War and, as far as the Unionist political elite was concerned, it would be this that would ensure that the new Northern Ireland would remain in the UK.

For Unionists, the main threat in the new six-county territory did not lie with Irish Nationalists. Their opposition to partition and the very existence of Northern Ireland was plain from the beginning, and Unionist priorities fixed on securing the loyalty of their own side, rather than on persuading the Catholic and Nationalist community to soften their antipathy to the Government of Ireland Act’s provisions. Nationalist discontent was taken for granted; the overriding task for Unionism was to prevent fissures opening up within their own ‘bloc’. This meant in particular focusing on the dangers of social class divisions and their possible exploitation by Labour candidates at election time.

Labour’s Challenge

Standing in the 1921 contest were a number of ‘Independent Labour’ candidates. They included Harry Midgley, whose future career was to see him lead the Northern Ireland Labour Party (NILP) in the 1930s and early war years, leave to form the ‘Commonwealth Labour Party’, and then join the Unionist Party and serve in cabinet offices.

However, in 1921 Midgley campaigned along with two others, James Baird and John Hanna, in opposition to partition. The three made strident proclamations in the Irish News, the Nationalist community newspaper, about love for their ‘native land’, and they condemned ‘Craigite and Carsonite policies’. ‘We are completely against partition’, they stated. ‘It is an unworkable stupidity as the inner circle of political wire-pullers well know’.

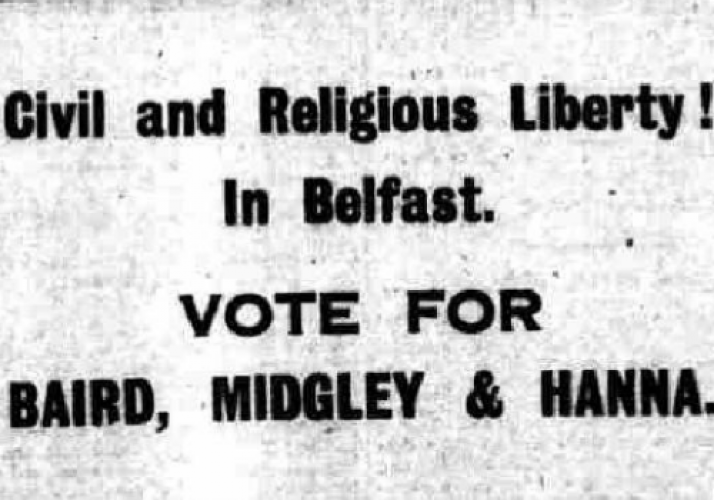

The Labour trio, it should be said, still tried to make a pitch to Protestant and Unionist workers: in the Unionist press their adverts made no mention of partition and instead made the following carefully crafted appeal: ‘Civil and Religious Liberty! In Belfast. Vote for Baird, Midgley and Hanna.’ Indeed, playing to the respective religious and national sensitivities of Protestant and Catholic workers would become a stock-in-trade of the NILP after it emerged in the mid 1920s.

The Unionists focused much of their campaigning energy on these Labour candidates. The post-war years had witnessed various happenings that highlighted the growing prospect of class friction and a rise in socialist activity across the sectarian divide: the 1919 ‘40-hour week’ strike brought Belfast to a halt; a group adopting the name ‘Belfast Labour Party’ won 10 seats at local elections in 1920; the May Day rallies in 1919 and 1920 boasted unprecedented numbers; unemployment accelerated as staple industries went into a slump.

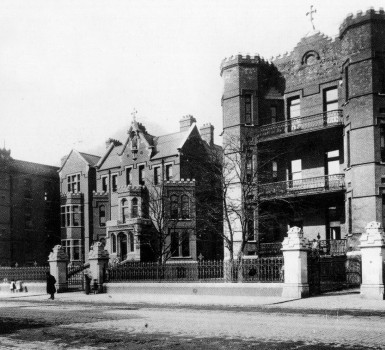

Against the backdrop of such developments, the Unionist Party placed much onus on the Ulster Unionist Labour Association (UULA). Edward Carson had been instrumental in forming this body in 1918, for the express purpose of nullifying the potential threat posed from the left of the political spectrum. In the 1921 election, the return of four UULA candidates was a particular source of satisfaction to the Unionist leadership, along with the derisory vote ultimately recorded for the independent Labour standard-bearers. The UULA played a central role in the hounding of Baird, Midgley and Hanna, alleging that they were in league with Sinn Féin and funded by ‘Dublin Gold’, and breaking up a Labour rally in the Ulster Hall a week before polling day.

‘Step by Step’

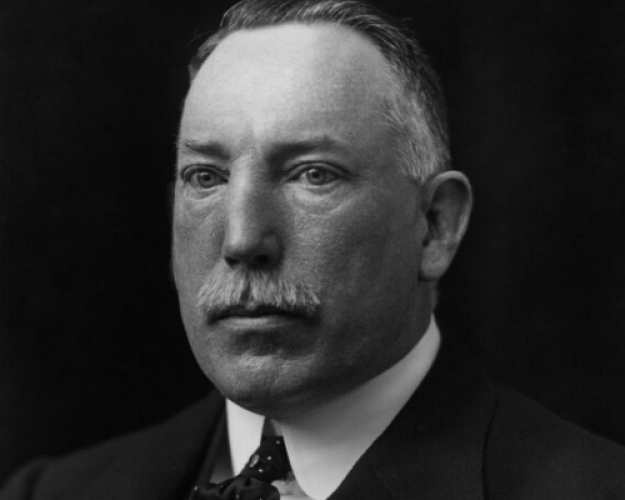

Following the election and the formation of the first Northern Ireland government, the UULA was presided over by John M. Andrews, who became Minister of Labour. Belonging to a famous County Down family, which had made its name in the linen industry, and brother of Thomas, the ‘Titanic’ designer, John M. Andrews would later become Northern Ireland’s second Prime Minister during the Second World War, following the death of James Craig in 1940.

Before reaching the top job, Andrews proved to be a key player in Northern Ireland’s successive Unionist governments. More than anyone else, except perhaps Craig himself, Andrews stood for a ‘step by step’ policy of maintaining social welfare benefits at the same level as the rest of the UK, of reproducing most of the Westminster legislation pertaining to working-class living standards, and of insisting on the same citizenship entitlements for the people of Northern Ireland in spite of the region’s anomalous position as a devolved entity.

For Andrews, the achievement of Unionism’s goals rested on the steadfastness of its working class voters. In his capacity first as Minister of Labour, then Minister of Finance, Andrews cajoled the British Treasury into effectively guaranteeing the payments necessary to preserve British standards of social services. This enabled Unionists comfortably to fend off the challenge of Labour locally.

What it also could be said to have done was position Northern Ireland to share in the markedly greater social benefits that flowed from the Labour government’s welfare state reforms and expansion of educational opportunities after the Second World War. These post-war reforms also benefited the minority community in Northern Ireland, providing perhaps the best opportunity for improving community relations since devolution’s inception. A combination of Unionist failure to think long-term, and continuing anti-partitionist campaigns of different kinds, was to prevent this opportunity being taken.