Focus On... Violence

23 August 2021

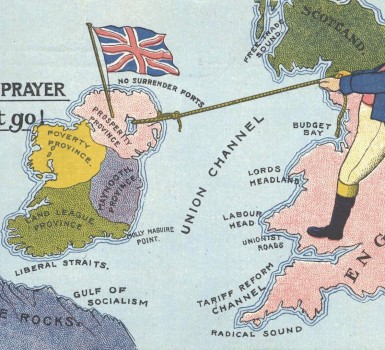

The years surrounding the creation of Northern Ireland a century ago are synonymous with violence. Between July 1920 and June 1922, a period which saw both the conclusion of the War of Independence and the beginnings of civil war in the 26 southern counties of Ireland, the six north-eastern counties that became Northern Ireland were beset by political and sectarian conflict. This violence, though nothing new to the north of Ireland, would prove the fiercest and most prolonged spell of communal hostility in the region until the late 1960s.

Though violence took place throughout Northern Ireland, Belfast was the epicentre of the new region’s ‘troubles’. In July 1920 the IRA murder of the controversial Lieutenant-Colonel Gerald Bryce Ferguson Smyth, the RIC’s commissioner for Munster with family links to Banbridge, Co. Down, spawned an outbreak of severe sectarian violence. On 21st July thousands of Catholic ‘Sinn Féiners’ were expelled from the shipyards and other Belfast industries, sparking three days of intense fighting and rioting, and the intervention of crown forces in the city. A second wave of violence in Belfast and Lisburn a month later brought the total number killed in the summer months to 40, with many more left injured, homeless, or jobless.

Intermittent violence continued for most of the following two years, reaching its height in July 1921 as the declaration of a truce between Irish republicans and British armed forces resulted in a week of almost continuous street warfare in Belfast, including what is now known as the city’s ‘Bloody Sunday’, which left over 28 dead and 100 wounded.

Below you can find a range of contemporary sources and viewpoints exploring different aspects of violence in Ireland in 1921. While unionists condemned the IRA as a ‘murder gang’ and ‘assassins’, by 1921 many British newspapers were becoming increasingly critical of the ‘terror’ committed by crown forces in Ireland ‘in our name’.

Violence in Ireland in the early 1920s must also be placed in the turbulent global context of the aftermath of the First World War. Following the collapse of the Russian, Ottoman, and Austro-Hungarian empires, newly created nation-states such as Poland, Yugoslavia, Lithuania, and Finland also experienced violent beginnings – largely focused on borders and ethnic minorities – as they sought to assert their national self-determination. In several cases, the violence witnessed in civil wars elsewhere was significantly worse than what happened across the island of Ireland.

Finally, Northern Ireland’s violent birth was not limited to the political realm, and a focus on political violence can obscure some of the other forms of violence that were widespread across the region. Armed robbery was on the rise in Belfast in 1921 (though as the Belfast Telegraph sarcastically notes below, this could also have political connotations), and domestic and marital violence was, in the words of the historian Rosemary Cullen Owens, ‘widespread and brutal’. It is extremely difficult to find instances of reporting on domestic and marital violence. The dominance of conservative social and religious cultures in the region were barriers to women, the main victims, reporting on their culprits, who so often were male relatives. The perceived sanctity of the home and the reverence for the institution of marriage were contexts where blind eyes were turned to abused women, just as the societal reverence for other religious institutions and their members permitted violence to be committed against young boys until the end of the century. As in the later ‘Troubles’, the notion that these types of abuse and violence were somehow less important than the violence being waged as part of the constitutional struggle has resulted in an inequity of memory and redress which Northern Ireland continues to grapple with today.

Belfast’s ‘Bloody Sunday’

Belfast Shooting Outbreak, Westminster Gazette, 11 July 1921

What, it may be hoped, will be the last desperate shooting outbreak in Belfast broke out early yesterday morning, and continued with more or less violence till the early hours of this morning.

Sixteen persons were killed.

Over 100 were wounded with shots.

42 houses were burned.

It is suggested that a number of persons, who also lost their lives, are not accounted for, but that the bodies were taken into houses during the firing.

The fire brigade was called out seven times, a number of houses in the Sinn Fein quarter being set on fire by Loyalists.

A party of Sinn Feiners who were digging in the street were surprised by Auxiliaries, and immediately fled, leaving behind them a number of sandbags, evidently intended for parapets.

Several children were wounded by snipers, who also hampered the movements of the fire brigade.

The situation finally became so threatening that military aid was requisitioned, and infantry were sent to the scene.

This is Belfast’s holiday week, and all industrial works are closed.

The Peril of Belfast

Belfast Telegraph, 15 July 1921

It is high time that very drastic steps were taken by the authorities to deal with the Sinn Fein gunmen who are attempting to terrorise Belfast. Thursday’s scenes in the centre of the city showed how daring these people are becoming, because in broad daylight they deliberately invaded Royal Avenue, firing revolvers, throwing stones, and creating general pandemonium. Law-abiding folk on legitimate business were in imminent peril, and it was only by the mercy of God that the casualty list was not heavier. These scenes were but the climax of a day of anxiety and unrest in the immediate neighbourhood. During the hours of Curfew on Thursday the gunmen made night hideous, and through the day the snipers rendered life unsafe by sending shots into the Unionist streets off York Street. Women and children were in terror, and final the gunmen, after wounding several persons, took the life of a young Protestant girl at the corner of Nile Street. Two or three hours later Mr. W. Grant, M.P., one of our most respected citizens, who with Mr. Thompson Donald, M.P., had been doing his best to pacify the affrighted people, was shot while proceeding to look for military protection for the Loyalists.

The reckless manner in which rifles and revolvers were used by the gunmen has created a feeling of irritation, and it is not surprising that with the limited means at their disposal Loyalists did their best to protect themselves. There appears to be no limit to the supply of ammunition on the rebel side, and frankly we do not see much prospect of peace till these gunmen are rooted out. The whole business looked suspiciously like a plot to discredit Belfast and Ulster at this juncture. There is a tendency amongst many English people, largely the results of the lying reports in anti-Ulster papers in London and elsewhere, to believe that everything that happens in Belfast must be put down to the Unionists…

The Crimes of Sinn Féin

Belfast News-Letter, 2 August 1921

To the editor of the Belfast News-Letter.

When Nurse Cavell was murdered by the Huns the British nation was horrified, and justly so. The assassins were then condemned equally by the pulpit, the Press, and by “the man in the street.” Today, when the murder gang in Ireland have openly admitted that they have murdered Mrs. Lindsay, of Cork, there not word of protest or condemnation from Church or State; the assassins are left unpunished, while England, Mother (?) England, who has formerly stood for the principles of justice and right, grovels at their feet and kew-tows to the leaders of a society which could beat savages in barbarity and brutality. Have our loyalist MPs all become dumb? Has the Press taken a vow of silence? If not it is high time for them to cast apathy aside and speak in no uncertain voice against the crimes of Sinn Fein.

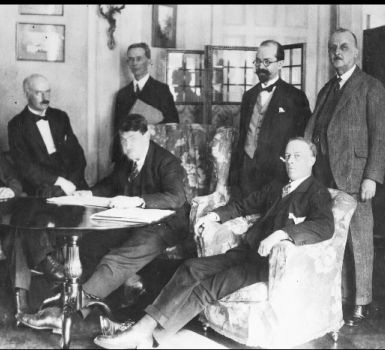

Debate between Chief Secretary of Ireland Hamar Greenwood and the Nationalist Party MP for South Down Jeremiah MacVeagh, House of Commons, 16 February 1921, Hansard’s Parliamentary Debates, vol. 138 cc 93-4

Mr. MacVEAGH (by Private Notice) asked the Chief Secretary whether he has received any report of the robberies and personal violence committed by special constables in the town of Newry; whether these charges have been preferred by leading merchants; and whether an independent investigation will be held?

Sir H. GREENWOOD: The serious allegations which have been made against certain units of the Special Constabulary in the Newry district have already been the subject for official inquiry, and as a result one platoon has been disbanded and a number of men are now awaiting trial by court-martial on charges of theft. In regard to the second part of the hon. Member's question the Military Court of Inquiry held in lieu of inquest into the deaths of the two internees at Ballykinlar found that no blame attached to the soldier who fired in the execution of his duty. No action of punitive or disciplinary character was therefore called for and none has been taken. ...

Mr. MacVEAGH: Has any action been taken in the case of the soldier who shot dead two interned prisoners in the Ballykinlar camp?

Sir H. GREENWOOD: The military inquiry held in lieu of the inquest found that no blame attached to the soldier, who fired in the execution of his duty.

Mr. MacVEAGH: Is it not a fact that Colonel Little, the commanding officer, agreed that these prisoners should be allowed to converse with the prisoners in another camp provided that they did not approach the wire entanglements; and that these two men were shot dead by the soldier, without any order from the officer, whilst they were 40 feet away from the wire entanglements?

Sir H. GREENWOOD: I must ask the hon. Member to give me notice.

Mr. MacVEAGH: Was the soldier who shot these two men put on trial? Was he court-martialled?

Sir H. GREENWOOD: Any soldier who is accused is at once relieved of his duty until the hearing of the case. I have already said that no blame attached to the soldier, who fired in the execution of his duty. Every opportunity was given to the internees to give evidence at the inquest, but no one responded.

Mr. MacVEAGH: Is not the reason for that because no one had the slightest confidence in the impartiality of the tribunal? Is it not a fact that this inquiry was conducted by the officers of the man who committed the two murders?

Commander Viscount CURZON: Is it not a fact that the soldier fired only after repeated warnings to these two men?

Sir H. GREENWOOD: That is so.

Mr. MacVEAGH: That is not so.

… Mr. MacVEAGH: Is it not a fact that the relatives of the two men who were murdered were not informed of the murders until three days after they had taken place?

Sir H. GREENWOOD: I am not aware of that.

Irish Reprisals: Galway victim’s story of his experiences, action of Crown Forces

Westminster Gazette, 30 April 1921

Mr P. Moylett has a letter in the Times today, in which he retails his experiences as a victim of the Irish Terror. Mr Moylett, who declares that he keeps rigidly to what has happened to his family, himself, and to the business concern in which he is senior partner, tells without feeling a story which should make the blood of any freedom-loving Englishman boil…

‘Violence in our name’

Sir John Simon, addressing University students at Birmingham University last night on reprisals, said that those who recalled with horror some things done by the Germans during the war must not shut their eyes to what was going to be said about us if we did not protest with all our might against the violence which was being perpetrated in our name in Ireland. He pleaded for a truce and an endeavour to secure peace.

Crime in Belfast

Belfast Telegraph, 6 August 1921

Three serious cases of robbery under arms occurred on Friday night in Belfast, and in one of these where resistance was offered the gang did not hesitate to shoot, with the result that two business men, in their offices at College Court, were seriously wounded. An unfortunate feature of the raid is that the thieves were not caught red-handed. Crimes of this sort are due to the fact that there are so many revolvers at large in the city. Dublin is passing through a similar experience at the hands of revolver men, acting on their won. At the Green Street Commission on Friday the Lord Chief Justice sentenced a man to two years’ hard labour for assaulting a laundry manageress with a revolver and stealing £15 from her. Earlier in the week the same judge sentenced an entire gang for similar offences all over the Metropolis. Crimes of this description ae a menace to public safety, and will have to be sternly dealt with. Courts-martial have marked their sense of them by very heavy sentences, but the punishment meted out in some of the civil courts has been on a very different scale, and that does not at all coincide with the public view of the enormity of these offences. Some of the sentences passed in revolver cases at Belfast during the present year have been outstanding in their leniency. But we live in strange times, when the police are prevented from arresting men suspected of robbery under arms because the motive was said to be political. There was actually a case in Belfast the other day where a prisoner, charged with the Great Victoria Street Post Office robbery, was released because he had been arrested during the truce. We never knew before that the association between robbery and politics was so close; but evidently the stealing of money from post offices is recognised by the Government as part of the “war.”

The serious occurrences of yesterday were followed to-day by an equally serious affair, in which a policeman was shot in the Knock district. There is no evidence at the moment of writing as to the motive, but the fact that such a crime was committed shows the risk run by the police. There can be no question of truce in this case, and we trust that the miscreants will be run to earth. There has surely been sufficient shooting in the city, without a renewal of it by burglars or other evil-disposed persons.

Derry painter charged for Alleged assault on wife

Londonderry Sentinel, 8 March 1921

At Londonderry Petty Sessions yesterday Margaret Donnelly, 16 Chamberlain-street, summoned her husband, Patrick Donnelly, a painter, for assault, and William Gallagher summoned Donnelly, who is his son-in-law, for threatening language.

Mrs. Donnelly said she lived with her father at 16, Chamberlain-street. About 6.45 o'clock p.m. on the 24th February her husband came into the house after being out the whole day. She asked him where he had been all day, and he said, "What —— is that your business?" She said he should have come in for dinner. He told her she had a cheek to talk to him, and used very filthy language. Witness's father said there would be no more of this trouble in the house. Defendant, who was under the influence of drink, took off his coat, and lifted his fist to hit his father-in-law. Witness subsequently lifted the coat and threw it to the hall, and told defendant to go away. Defendant hit her with his fist and blackened her arm. Witness added that she had trouble all her life with the defendant.

Dr Ryan Mallon, Queens University Belfast