The First Northern Ireland Parliament

18 June 2021

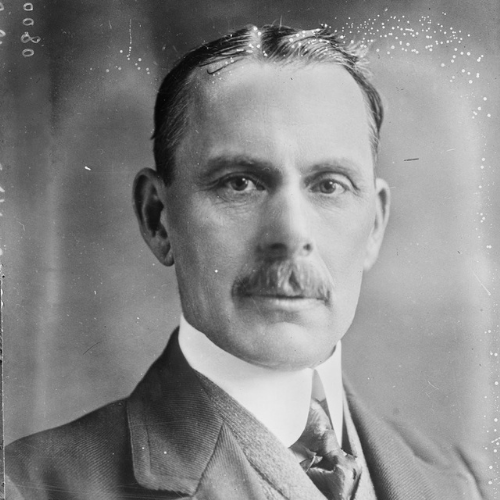

John Miller Andrews (1871-1956)

John Miller Andrews belonged to a famous County Down family which was prominent in the linen industry. He was the eldest son of Thomas, one of Ulster Unionism’s leaders in the fight against Irish Home Rule before the First World War. His brother Thomas was the designer of the ill-fated Titanic. John M. Andrews would become Northern Ireland’s second Prime Minister during the Second World War, following the death of Lord Craigavon.

Before reaching the top job, Andrews proved to be a key player in successive Unionist governments, first as Minister of Labour, then Minister of Finance. He was probably the keenest advocate of the ‘step by step’ policy of maintaining social welfare benefits at the same level as the rest of the UK, and of reproducing most of the Westminster legislation relating to working class living standards. He was also the paternalistic, guiding figure behind the Ulster Unionist Labour Association (UULA).

His premiership was blighted by the catastrophic effects of the Nazi bombing of Belfast in 1941 and his government’s dithering response. By 1943 he had lost the confidence of the Ulster Unionist parliamentary party and was forced to give way, as PM and leader of the party, to Basil Brooke. However, he remained a stalwart of the Ulster Unionist Council (UUC) until his death, and was an MP in the Northern Ireland parliament until 1953.

Graham Walker, Queen's University Belfast.

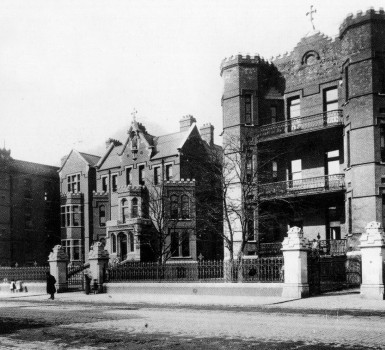

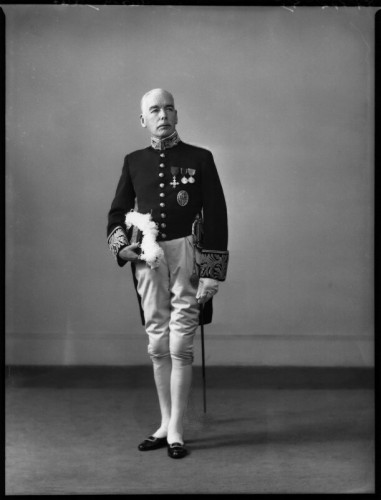

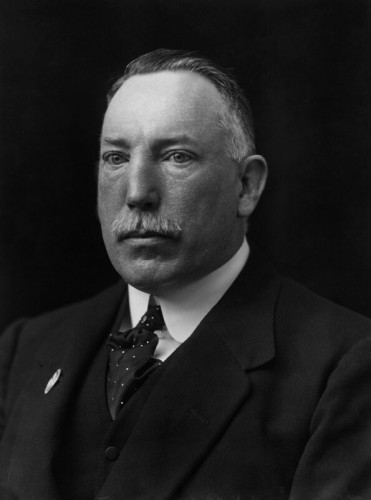

Sir Richard Dawson Bates, 1876-1949

A Belfast solicitor, secretary of the Ulster Unionist Council 1906 to 1921. Responsible for the organisation of the Ulster Covenant in 1912. Knighted 1921. Stormont MP for East Belfast from 1921 to 1929 and Belfast Victoria from 1929 to 1943. J.F. Harbinson (The Ulster Unionist Party 1882-1973, Belfast 1973, pp. 50-7) offers this description of Bates: ‘A small man, physically and intellectually ... His great strength was his meticulous attention to detail... he was the grey eminence of Ulster Unionism who remained in the shadow of Carson and Craig.’ Bates was widely considered to be the least enlightened member of the Cabinet, though even he acknowledged, in private conversation, the serious ‘menace’ of the Ulster Protestant League. (PRONI D2661/C/1/M/11) He also effectively dismissed the partisan policeman D.I. Nixon by promoting a Catholic policeman D.I. Regan above him.

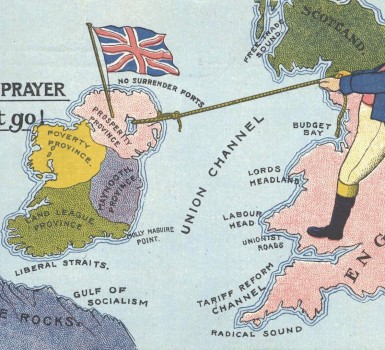

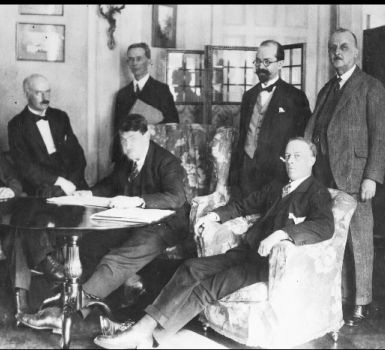

Sir James Craig (Viscount Craigavon), 1871-1940

Prime Minister of Northern Ireland. During his premiership (1921-40) Craig successfully impressed his personality on the institutions of government in Ulster. In February 1921, shortly before becoming Prime Minister, he declared: ‘The rights of the minority must be sacred to the majority… it will only be by broad views, tolerant ideas and a real desire for liberty of conscience that we here can make an ideal of the parliament and executive.’ But his political life was dominated by a fear of internal Protestant schism and unfortunately in his later and least impressive years he found it difficult to maintain this early spirit and his rhetoric and that of his ministers often caused offence within the Catholic community.

Craig was the son of a Presbyterian whiskey millionaire and educated at Merchiston in Edinburgh. In 1906 he won his parliamentary seat (for Down East, which he held until 1918) in a close contest with an agrarian radical Unionist, James Woods; his speeches on the land question in this period place him firmly in the realistic and reformist wing of Unionism. Amid the ranks of Conservative and Unionist MPs demoralised and decimated by the Liberal landslide, the energetic Craig found it relatively easy to make a name for himself at Westminster, principally as a vigorous opponent of Home Rule. Devolution for Northern Ireland after 1921 ended this phase of his career. Although, like many other Unionists, Craig was reluctant to accept such a settlement of the Irish question, he rapidly made a virtue of necessity. His political concerns became increasingly parochial and ‘little Ulsterist’ in outlook and he became more-or-less indifferent to the wider interests of Great Britain and the empire.

As the Free State moved towards the adoption in 1937 of what one of its ministers (Sean McEntee) was happy to describe as ‘a Catholic constitution for a Catholic state’, Craig was equally happy to talk of ‘a Protestant parliament for a Protestant people’. His style of work became increasingly casual; he distributed ‘bones’ to the ‘dogs’, as he once described his operation of the spoils system.

Craig in his earlier years enjoyed a promising career outside Ulster. From 1900 to 1902 he served with distinction in South Africa and by 1920 he had become Parliamentary and Financial Secretary to the Admiralty. It is hard to resist the conclusion that the return to Ulster narrowed his horizons. In this he resembled his great local nationalist rival, Joe Devlin, who had, if anything, an even more promising Westminster career between 1900 to 1918 and was equally shrivelled by the devolution experiment which made him little more than a local tribal leader.

Joe Devlin, 1871-1934

Joseph Devlin was born in Hamill Street, Belfast, educated at Divis Street Christian Brothers’ school and began his working life as a barman, but soon became a journalist for the Irish News. He emerged rapidly as a leading figure in Belfast nationalist politics; in the early 1900s Devlin pitted his resources against the Belfast Catholic Association, the political machine of the local bishop. This revealed his deep hostility to any form of factionalism – in this case a sectarian one – within nationalism. In an article in the Leader (19 February 1910), Francis Cruise O'Brien observed of Devlin's anti-factionalism: ‘He confuses adjectives with arguments and consequently there is no weight in what he says... Ideas to Mr Devlin spell faction. To suggest that his methods are not wise methods and that sometimes they are not creditable methods is to sin the unforgivable sin against Ireland.’ After 1902, when he became an MP for Kilkenny, and then from 1906 to 1918 as representative for West Belfast, Devlin was an equally bitter opponent of a rather different figure – the pluralist and conciliatory William O'Brien and his nationalist All for Ireland League of MPs. During the Home Rule crisis of 1912-14 Devlin was a major figure; he used his influence to stop Redmond from accepting a partitionist settlement, yet by 1916 he himself appears to have been convinced that it would be a mistake to coerce Unionists into a united Ireland. He remained, however, a firm opponent of the establishment of any local parliament. At times Devlin made efforts to work in the Northern Ireland parliament, but always rightly felt that his overtures received a less than generous response from the Unionist elite. His death, however, seemed to provoke a genuine sense of grief in Craig.

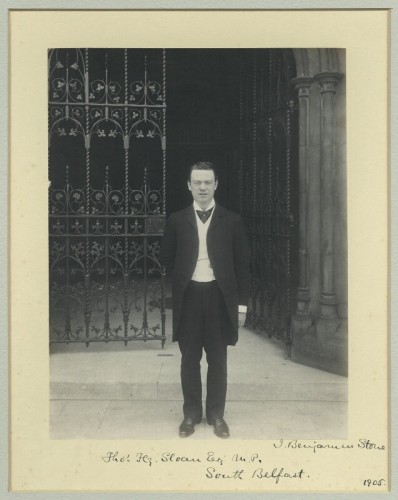

Hugh Macdowell Pollock, 1852-1937

Stormont MP for South Belfast 1921-29 and Belfast Windsor 1929-37; Minister of Finance in the Northern Ireland government 1921-37. Described by Sir Robert Kennedy in 1937 as ‘a good financial accountant for all local purposes but he is old, cranky and tactless’ (P. Bew, K. Darwin and G. Gillespie (eds), Passion and Prejudice, Belfast, 1993, p. 4). Hugh Pollock was the most intellectual and well read of the Unionist cabinet ministers. A convinced Federalist, he feared the consequences of growing Belfast dependence on the London exchequer. John Andrews argued for the doctrine of parity with the UK on economic and social services. Pollock was unenthusiastic. His technical skills were, however, very helpful to Belfast shipbuilding finance.

Paul Bew, Queen's University Belfast.