The Forgotten Partition of Orangeism

12 July 2021

Dexter Govan, University of Edinburgh.

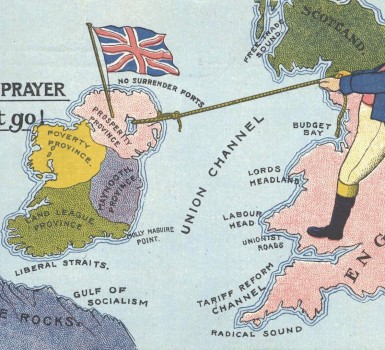

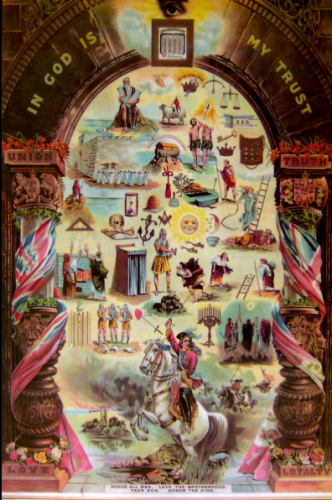

In many ways 1921 marks beginnings. A new state and government, a new border, a new Northern Ireland. But for the Loyal Orange Institution, or the Orange Order as it is more popularly known, the year was the end of a journey in Ireland-wide Unionism. Founded in 1795, the Orange Order existed to defend Protestantism and civil and religious liberty across Ireland. It followed the template of other homosocial societies before it, building lodge halls and cloaking itself in costume and ritual. Though unlike the Freemasons or the Ancient Order of Foresters, it was devoutly Protestant.

The Qualifications of an Orangeman, the principles for membership of the Order, were not concerned directly with constitutional politics. They contained no mention of borders, states, or partitions. Instead, they stressed the importance of sincere religious faith: of a commitment to God without mediator. Alongside this was a militant opposition to Catholicism. All Orangemen were to “strenuously oppose the fatal errors and doctrines of the Church of Rome”. Nor were they to countenance by their presence or otherwise, “any act of Popish worship”. In theory at least this opposition was theological and directed at Catholicism and not Catholics. In practice, the two were often confused and the Order took on martial characteristics.

The process of partition wasn’t just an exercise in creating two jurisdictions on the island of Ireland. The Orange Order participated in its own partitioning exercise. In 1911, northern Orangemen, led by future prime minister James Craig, sought more power within the Order. They created a new body, the Provincial Grand Lodge of Ulster, which would manage Orange affairs in the north. Voted through despite opposition from Dublin, Orangemen in the nine counties of Ulster used the new lodge to support the work of the Ulster Unionist Council, to facilitate the drilling of Orangemen and later to recruit Orangemen into the Ulster Volunteer Force. It isolated the scattered Orangemen of the south of Ireland from their northern stronghold. Without that attachment, southern Orangeism faded into comparative obscurity.

By partitioning the Order in this way Craig had done little but entrench existing divides in its membership. That the Orange Order abandoned an all-Ireland Unionism a decade ahead of the partition of Ireland is revealing. Unionism was changing, consolidating itself in the north.

This process was accelerated during the First World War. Enlistment was high among the Order’s membership, and so were casualties. While in Ireland women’s Orangeism was growing slowly after 1912, in Scotland it had thrived since 1909. During the war, Orangewomen devoted themselves to charitable work and in support of the armed services. Indeed, within gendered constraints, Orangewomen exercised a remarkable degree of autonomy in what is often considered a very socially conservative institution. The number of Orange causalities in the war, combined with the success of women’s Orangeism in these years meant that in Scotland, Orangewomen would come to outnumber Orangemen for two decades. But if the War encouraged Orangewomen’s activity, in the south of Ireland its casualties effectively sealed the tomb of Orangeism outside of Ulster.

After the war, and in renewed constitutional turmoil, members of the Order attempted to return to their religious practice, to the social life of Orangeism and a form of normality. Orange bazars and galas fundraised for charities. Orange Lodges dedicated to temperance continued to be popular. In Belfast around half of all Orange Lodges abstained from alcohol, though Twelfth of July parades frequently saw considerable drunkenness. These were the two sides to the Order, a “rough” and “respectable” duality. So called “Orange services” in Protestant churches continued to emphasise the religious tenets of Orangeism.

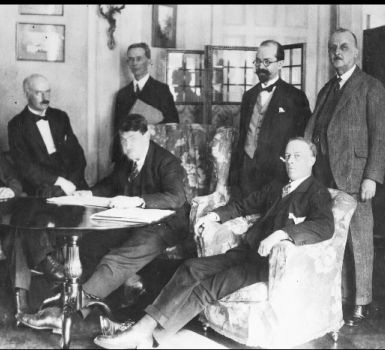

Politically the Order followed Ireland-wide Unionism in the years between the creation of the Provincial Grand Lodge of Ulster in 1911 and 1920. By 1920 however, it was prepared to sacrifice Cavan, Donegal and Monaghan to create a Protestant super majority for a new state. Orangemen in Cavan and Monaghan protested this, but their pleas went unanswered by the Grand Lodge of Ireland. Those in charge of the Order after 1921 prioritised protecting the new and fragile Northern Ireland state from republican and Roman incursion above these abandoned counties. Though the Order continued to be an all-Ireland body, with many lodges still operating in Cavan and Monaghan, power became increasingly centralised in Belfast. In 1921, the Grand Lodge moved its headquarters there from Dublin, a physical symbol of this ideological shift.

This mirrored wider Unionist politics, as James Craig came to replace Edward Carson. Years later, in a now infamous speech, Craig would declare that he was “an Orangeman first and a politician and member of parliament after”. However much this was true, Craig was a vessel through which first the Orange Order, and later Ireland itself had come to be partitioned.

In many ways 1921 marked a new beginning for the Orange Order. With James Craig at the helm of the new Northern Irish state, the Order’s often fractious relationship with state power would settle into a formidable alliance in the years following partition - the “Orange State” as it has sometimes been called. But every bit as profound, by 1921 the Order had abandoned all-Ireland unionism. While 1921 saw new beginnings for the Orange Order, it had also seen the effective end of its Ireland-wide journey.