Tourism in Ireland

07 September 2021

In Ireland, tourism has often been a way for marginal regions to bring in visitors and investment. In 1909, the Health Resorts Act was passed in Parliament which allowed Ireland’s local authorities to devote 1% of their local rates to advertising for tourists, a privilege not granted to most British authorities until the 1920s. Predictably, the towns and regions most keen to use this legislation were coastal resorts or well-established destinations.

By 1915 of the twelve Irish local authorities using the 1909 Health Resorts Act to advertise themselves, five of them were from the future Northern Ireland. Tourist numbers slumped during the War of Independence and Partition, but quickly picked up again after 1924. In 1923 the Local Government Act (Northern Ireland) raised the maximum rate on advertising by local authorities from 1% to 3%, a recognition of the importance of tourism to many towns and coastal areas.

A Struggle for Recognition

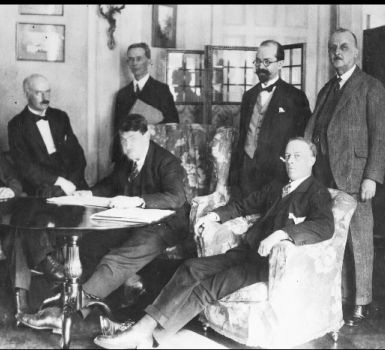

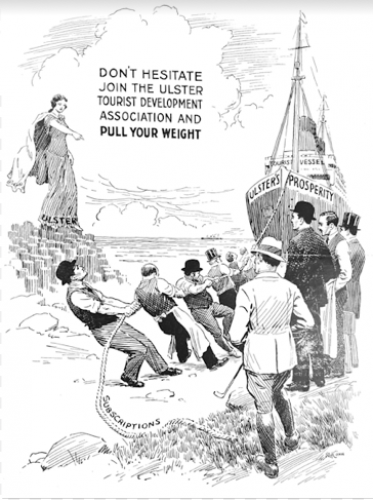

The Northern Ireland government had begun promoting tourist development in 1922 through its unofficial mouthpiece, the Ulster Association for Peace with Honour, who published an ‘Ulster Gazette’ with business, political and tourist information. In 1924, members of the Ulster Association for Peace with Honour then founded the Ulster Tourist Development Association (UTDA), a voluntary body maintained by subscriptions from local councils. Despite being enabled to grant almost 3% of revenues by the new Local Government Act, most councils subscribed only token amounts to the UTDA. To compensate, the UTDA received an annual grant from the Northern government, beginning with £500 and eventually rising to £4000 in 1938.

In addition to general indifference to tourist development, and the fact that councils saw it as a matter left purely to ‘private enterprise’, the UTDA faced criticism for its use of the name ‘Ulster’. Lord Belmore, a Fermanagh unionist who had opposed the partition of nine-county, historic Ulster, frequently called the UTDA “disgraceful” and “dishonest” for using the title of Ulster, and the newspaper coverage of Belmore’s outbursts suggests a certain amount of sensitivity over the abandonment of Ulster’s “lost three” counties of Donegal, Cavan and Monaghan. Without calling for an end to partition, many called for closer cooperation with Irish tourist promoters, especially the UTDA’s southern equivalent, the Irish Tourist Association. The UTDA and Northern government officials were nervous to endorse this, and until the 1960s, tourist cooperation between North and South was limited to sending delegates to annual meetings as a token of the “cordial relationship” between the UTDA and the ITA.

Propaganda and Identity

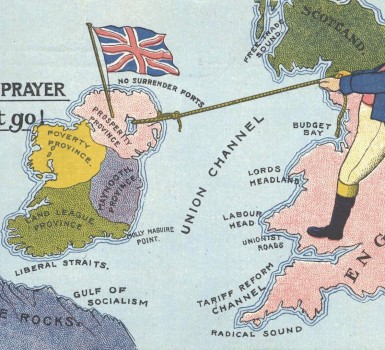

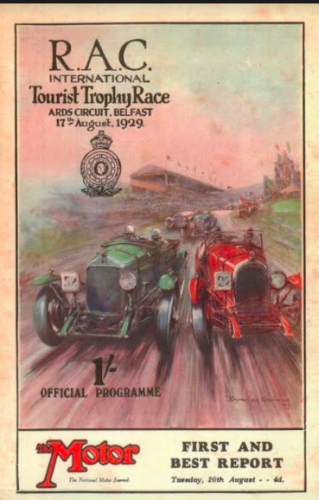

Tourist literature has often been a potent propaganda tool and was employed by both unionists and nationalists before and after partition. ‘Ulster Guides’ produced by the UTDA mirrored earlier books which combined dense topographical descriptions with non-contentious heritage such as stone circles and ruined castles. Political undertones were however apparent in the guides through the inclusion of a Prime Minister’s ‘Foreword’ explaining Northern Ireland’s constitutional position, and the extensive coverage of the province’s industries and ‘go-ahead’ seaside towns. The UTDA also sponsored films such as those made by the actor Richard Hayward, who wanted to combine traditional representations of ‘Irishness’ with recognition of the modern, ‘progressive’ identity of the new Northern state. The Northern government also passed legislation and sent ministers to lobby for motor racing events to be held in Northern Ireland, such as the Ulster Grand Prix (for motorcycles) and Ulster Tourist Trophy (for motor cars).

Tourist posters sponsored by the UTDA were, at first, clearly ideologically opposed to typical depictions of Ireland. William Conor, who was commissioned to produce a poster for the UTDA in 1926, declared that he wanted to get “as far away as possible from the conventional Irish poster of shawled peasant and whitewashed thatched cottage and brown melancholy bog”. The UTDA held a number of poster competitions and those selected gave a vibrant, young new face to ‘Ulster’ in the form of young women enjoying liberating leisure pursuits such as golf and hiking. The first ‘competition’ poster chosen by the UTDA depicted a woman golfer standing in front of a map of the new Ulster, her head and shoulders deliberately cutting off the three “lost” counties. Over time these posters were replaced by professional productions which erased indicators of poverty as well as modernity in the landscape, thus following wider changes in tourist promotion.

Cross-border cooperation

The new border presented an obvious barrier to hopeful tourists, especially after customs posts were imposed in March 1923. On one occasion, two Americans were kept waiting for 3 hours at Belfast port before their luggage cleared. Travellers by car had to obtain a ‘triptyque’ from the Automobile Association in order to cross the border (this system was only abolished in 1959). Instead of lingering over trade barriers within Ireland, the UTDA and the Northern government preferred to stress that there were ‘no customs barriers’ for British travellers coming to Northern Ireland, a recognition of the fact that most tourists came from northern England and Scotland, but also a political statement of continued union with Britain.

In 1948, the Northern government recognised the need for an official tourist development body and followed the South’s example in setting up a statutory Tourist Board, with a permanent budget and staff, as well as a large development fund which would make grants towards constructing hotels or preserving other tourist facilities. This vastly increased the quality and quantity of promotional material, as well as the ability to respond to enquiries or help development in Northern Ireland. By calling itself the Northern Ireland Tourist Board, the new body avoided many of the problems which the UTDA had encountered, although it retained its partitionist focus since it was under the oversight of the Northern Ireland Ministry of Commerce. North-South tourist cooperation existed at an unofficial level, including sharing materials and carrying each other’s publicity at trade fairs and information offices, but it was not to be until the late 1950s that official cooperation became possible.

Jamie Nugent, Queens University Belfast